What Pope Francis and Ivan Illich prioritize in common: Anti-clericialism, the Global South and the cry of the poor

Who said it first? The call for the church to radically declericalize. The rejection of technocracy and the Western style of development. The concern with the cry of the poor, understood as victims of “the war on subsistence” in the Global South.

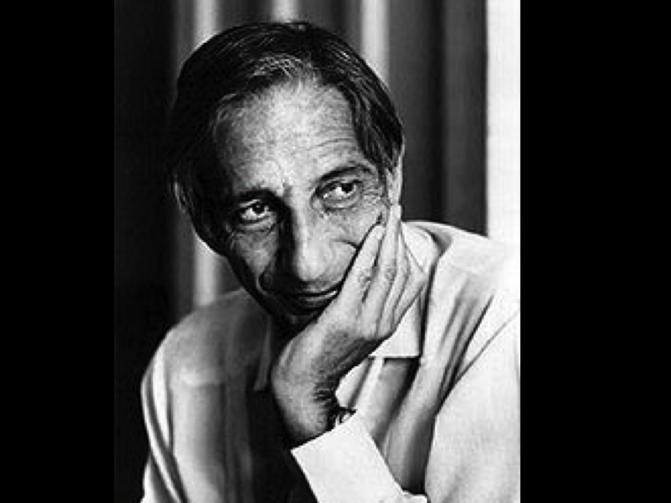

These are themes we associate today with Pope Francis, even if some of them appear in the proclamations of his two predecessors. But it was the Rev. Ivan Illich, a priest (assigned to the Archdiocese of New York under Cardinal Francis Spellman) and prescient social critic who came to prominence in the 1970s, who first sounded them in his writing and public speaking. A half-century later, some Catholic voices are belatedly claiming that Illich’s hour has finally arrived.

A student of Jacques Maritain and a “radically orthodox” monsignor who remained tradition-minded his entire life, Illich collided with the Vatican’s Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith in 1968 after the publication in the previous year of his articles “The Seamy Side of Charity” (in America) and “The Vanishing Clergyman” (in The Critic). The very titles hint at notions that must have been uncomfortable for the hierarchy.

Called to appear in Rome for an interview in a subterranean room, Illich recounted, he was handed a list of 85 questions that he saw as a farrago of rumor, innuendo and misinformation, partly based on U.S. Central Intelligence Agency documents and statements from right-wing Catholic groups in Mexico, including local Opus Dei adherents. Illich refused to answer the questions, choosing to remain silent in hopes of frustrating any further efforts by his enemies to create scandal or to de-platform him, as we would say today. Thereafter, Illich, contrary to popular impression, never renounced his priesthood but asked only to be relieved of his priestly duties.

Indeed, as the philosopher Giorgio Agamben argues in his introduction to a collection of Illich’s writings from between 1955 and 1985, “it’s not possible to mark any break between the Illich who is within the Church and the one who lies outside of it (or at its margins).”

Another of Illich’s notable disagreements with the institutional church dated to his time as an advisor at the Second Vatican Council while he was still in his late 30s. (Only a few years earlier, he had founded the famous Centre for Intercultural Documentation in Cuernavaca, Mexico; attendees included John Rawls, Peter Berger and Gustavo Gutiérrez.) When he was unable to influence stronger antinuclear language—specifically a stance for unilateral disarmament—in the key document of the council, the “Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World” (“Gaudium et Spes”), he withdrew from the council altogether.

In his 1967 essay “Vanishing Clergyman,” Illich asks:

Should I, a man totally at the service of the Church, stay in the structure in order to subvert it, or leave in order to live the model of the future? The Church needs men seeking this kind of conscious and critical awareness—men deeply faithful to the Church, living a life of insecurity and risk, free from hierarchical control, working for the eventual “disestablishment” of the Church from within.

While Illich chose the path of the outsider, the question of how to understand the church’s formative and even corrupting role as the ultimate historical source of many modern institutions remained a lifelong preoccupation.

New interest in Illich

We know much more about Illich’s intellectual journey—first as a critic of his own church, then as a public intellectual unveiling the counterproductive nature of the educational, medical and economic development establishments, and finally as an even deeper critic of the corruption of Christianity—through the brilliant achievement of the Canadian broadcaster David Cayley. His recent biography, Ivan Illich: An Intellectual Journey,written from his vantage point as a friend and collaborator with Illich, is a sorely needed contribution, a 500-page, incisive, literate analysis arriving as a blast of sanity.

Cayley’s book is in fact part of what we can hope is the second coming of Illich, even if his arrival in the U.S. Catholic conversation is still getting underway after all these years.

One of the first commentators to notice the congruity between Illich’s thought and the agenda of Pope Francis was Nathan Schneider in an insightful 2015 review of Todd Hartch’s Prophet of Cuernavaca for Lapham’s Quarterly. We should also note the wonderful Faith Seeking Conviviality: Reflections on Ivan Illich, Christian Mission, and the Promise of Life Together, by Samuel E. Ewell III, published in 2020. Ewell uses his “reverse missionary” experiences in Brazil as a lens to view the nature of Illichian conviviality and the themes of “Laudato Si’.”

One of the first commentators to notice the congruity between Illich’s thought and the agenda of Pope Francis was Nathan Schneider.

Another Catholic enthusiast for Illich is the theologian William Cavanaugh of DePaul University’s Center for World Catholicism and Intercultural Theology, where Cayley made a presentation on Illich’s Medical Nemesis in 2021. Cavanaugh’s podcast interview in 2022 with Cayley is a marvelous, highly informed exchange.

Likewise, Sam Rocha, a versatile younger Catholic scholar of education at the University of British Columbia, has a book forthcoming on Illich; he has already published an article on the latter’s relation to liberation theology.

Finally, L. M. Sacasas, writing from a Christian (but not Catholic) perspective, has been blogging about technology at his thoughtful and Illich-inspired Substack newsletter, The Convivial Society.

Interestingly, First Things—a publication whose history reveals little interest in unpacking American neocolonialism—has published two articles on Illich in recent years. The latest is a skillful review of Cayley’s biography by Brian C. Anderson, marred only by his slightly comic invocation of the uber-capitalist Peter Thiel against Illich’s critique of neoliberal economic development.

International reputation

While American Catholics may have been slow to discover Illich, figures in the global environmental and anti-growth movements have been citing texts like his Tools for Conviviality since it was first published in 1973.

In 2013, a conference on Illich’s thought in Oakland, Calif., brought together a notable group of thinkers and activists on “the commons”—i.e., our shared environmental and cultural inheritance. Hosted by then-mayor Jerry Brown, a longtime friend of Illich, the group included the commons advocate David Bollier, the post-development author Gustavo Esteva and the alternative economics author Trent Schroyer, in addition to Cayley. (Other notable figures who have feted Illich in past years include Pierre Trudeau, Indira Gandhi, Michel Foucault and Erich Fromm.)

Bollier’s longstanding commitment to defending the resources of the commons, as his website notes, owes much to Illich’s “critique of the totalizing power of modern institutions, the corrupting influences of capitalism on spiritual life, and the power of vernacular (i.e., informal) practice to build more wholesome, insurgent cultures.” Let’s pay attention to that last item.

When Pope Francis visited Amazonian Peru in 2018, coverage of the intercultural conversation included notice of the indigenous social philosophy known as buen vivir. The term—which also refers to a social movement—describes a vision of “good living” based on a balance and harmony with nature, and even recognized rights of nature, as now enshrined in the constitutions of Bolivia and Ecuador.

It is a philosophy often associated with the idea of the pluriverse, a loose framework (first put forward in 1996 by the Mexican anti-colonial Zapatista movement in the phrase “we seek a world in which many worlds fit”) to hold together alternative visions and epistemologies from across the Global South.

The framework of buen vivir is also an Indigenous response to what Illich saw, prophetically, as the 500-year “war on subsistence in the name of scarcity,” where a so-called scarcity justifies the devaluing of all traditional sociocultural forms.

This point about the risk posed by first-world notions of development to traditional lifeways may remind us of the statement in the working document of the Synod of Bishops for the Pan-Amazonian Region, held in 2019:

The quest of the indigenous Amazon peoples for life in abundance finds expression in what they call “good living” ( buen vivir). It is about living in “harmony with oneself, with nature, with human beings and with the supreme being, since there is an inter-communication between the whole cosmos, where there is neither excluding nor excluded, and that among all of us we can forge a project of full life.”

By the term subsistence, Illich means not abject poverty but rather a dignified, self-sustaining existence, one which is close to the vision—and the lived reality—of buen vivir.

Why Illich?

I would suggest that the church that will emerge from the current Synod on Synodality—and may it be the long-awaited “church of the poor” of which Pope Francis is only the latest advocate—should fully embrace the wisdom of its faithful son Ivan Illich in all its complementarity of tradition and innovation.

Take a key modern assumption: that human beings are made up of needs that society is organized to fulfill. What Illich saw at work here was the corruption of Christianity through large organizations—first the medieval church, and then the modern realms of medicine and education—owing to their attempt to institutionalize the Gospel. He frequently described this historical process by the proverb “corruptiooptimi pessima”—”the corruption of the best is the worst.”

Another dominating power at work today—technology and the underlying idea that our purposes require tools—likewise finds its origins in the sacramental theology of the Middle Ages, according to Illich’s remarkable analysis.

A living reception of Illich’s work requires that we transcend our hidebound categories of “left” and “right,” a task that perhaps the current synod will make easier, at least for people of good will. Catholics on the political left may have problems with Illich’s refusal to set aside entirely Christian dogma, which he saw as having the secondary and purely negative function of protecting faith from “the intrusion of myth.” But a greater shock awaits those Catholics on the political right who encounter Illich’s extraordinary engagement with what he called “the most powerful idol the Church has had to face in the course of her history”—in his phrase, “life as idol.”

‘Life as Idol’

Illich first took up this theme publicly in a 1985 talk before a meeting of social workers in Macon, Ga. Asked to begin with a prayer, Illich instead began with a curse. Raising his hands, as Cayley reports, Illich repeated three times, “To hell with life!” This was at a time when reverence for “life” was fast becoming society’s last acceptable popular piety, while the medical establishment was inserting itself further between the patient and his/her own death, now no longer a personal act. Illich believed this shift in the meaning of death had turned life into something new.

No longer an indefinable attribute of living beings, the word life had acquired a facticity, the status of real property capable of being owned, administered and controlled. It had become the certainty of certainties, or as the biologist Loren Eisley put it prophetically in 1959, a “last unbearable idol.” Life has been reduced to bio-life, even if the word retains its Christian aura. This displacement or perversion of revelation was, in Illich’s term, blasphemous.

Illich wanted to convince his listeners that life presented a direct challenge to the church. And yet he argued that the church itself was the source of the danger here in its embrace of a form of scientism (for example, claiming to know when life begins). Further, he described the church’s complicity in what he called the regular violation of the dignity of women through the use of ultrasound images to argue for the personhood of zygotes.

Cayley notes that this ideologized topic was one on which neither Illich nor he himself (in a broadcast for the CBC on the topic) were ever able to make themselves understood.

With regard to the pro-life movement, Cayley comments that Illich, “so far as I know, never felt the need to take a ‘position’ on abortion. What Illich wanted to defend was the privacy of the womb and the prerogative of women with respect to pregnancy.” Cayley adds, “He certainly was not ‘pro-abortion,’ as some have said, but I think it’s safe to say, though I know of no explicit statement on the subject, that he did not think abortion was within the competence of the state.”

Then what do we owe, in Illich’s view, to those who are contemplating abortion or suicide or euthanasia?

In a letter to his friend Anne Serna, O.S.B., the prioress of the Abbey of Regina Laudis in Bethlehem, Conn., Illich claimed it came down to what St. Benedict called “the mother of virtues”—namely, discretion or “the measured discernment of unique situations.”

By way of explanation, Illich related to Cayley an experience in which he successfully dissuaded an older woman who was considering suicide after expressing his disapproval of her plan. He later reflected, “I failed to respond to her freedom.... I took this headstrong woman’s question as one more attempt to remain in control. I now fear that I discouraged her from listening to the Lord whose calling she might have followed in spite of her complete ignorance of Him.”

Shortly thereafter, the woman contracted pneumonia, and, Illich observes, “the caring state could not leave her in peace.” Thus she ended by losing control of her own life at the hands of the medical establishment, which Illich had critiqued to such effect in his earlier Medical Nemesis.

On three similar occasions thereafter, he felt compelled to say to suicidal individuals, “I will not open the window for you, but I’ll stay with you.” This position of not helping, but standing by, “because you respect freedom,” Illich stated, “is difficult for people in our nice society to accept.” Measured discernment, after all, is much more difficult than simply asserting a rule. Especially, as Illich wanted us to understand, for people for whom life—now mostly diminished to “bio-life”—has become an idol.

A renewed Christianity?

Cayley views Illich as a proscriptive rather than a prescriptive thinker, generally diagnosing our ills rather than attempting to address our future. Still, he notes that Illich does suggest elements of a practice in which the Gospel is an invitation to a new way of life rather than the promise of a “redemption” that lifts us out of the common lot and into some privileged status. As Cayley puts it:

Illich, to me, is an example of a renewed Christianity.... This begins with his way of reading the Gospel, attentive to “the voice of an anarchist Christ” and his way of understanding the Church as an institution that, from its very early days, made itself “visible” in the world “according to the mode of a state or political entity.” Illich’s proposal was a sweeping “declericalization” and an ecumenical effort to “seek the visibility of the Church in the conscious evangelical interpretation of prayer,” understood as “the search for the presence of God.” He understood the Gospel primarily as an invitation to live in freedom rather than to invent law, bureaucracy, and pastoral edification on a previously unimagined scale.

We are approaching a post-Francis time in the church but not necessarily with the expectation of a renewed Christianity.

Nonetheless, I recently suggested to a thoughtful Catholic friend that he read Cayley’s biography as an introduction to Illich’s ideas. Encountering my friend a few weeks later, he thanked me, adding simply, “It has changed my life.”

Elias Crim is an editor, writer, translator and publisher who founded the national blog Solidarity Hall in 2013 and the podcast “Dorothy’s Place” (with co-host Pete Davis) in 2017. He also has a newsletter at solidarityhall.substack.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment