We need to reclaim the legacy of Christian nonviolence

For centuries, a consistent commitment to nonviolence was, at best, a marginal position within the Catholic Church. Rather than rejecting violence outright, bishops, popes, and theologians typically sought to provide moral guidelines for its rightful use. Drawing on thinkers such as Augustine of Hippo and Thomas Aquinas, they developed criteria for just and unjust wars, discussed norms for the appropriate use of violence by the state, and debated the moral limits of self-defense. Meanwhile, at the level of practice, Catholics in public office and the military, as well as countless ordinary faithful people, relied on these norms to guide their consciences—sometimes following them, sometimes falling short.

Yet, over the course of the 20th century, and continuing into the 21st, the Catholic Church, alongside other streams of Christianity, has moved increasingly in the direction of embracing nonviolence as a core tenet of the faith. How did this happen? Is it a mere novelty or a return to the fullness of the gospel?

The answer, it turns out, is complex. On the one hand, the teaching and example of Jesus, as laid out in the canonical gospels, provides a strong basis for nonviolence. In the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus condemns not only killing but even anger (Matt. 5:22) and advocates offering “no resistance” to evildoers: “If anyone strikes you on the right cheek, turn the other also,” he proclaims (Matt. 5:39). Later in the same gospel, as Jesus is being arrested, he forbids his followers from defending him with force, saying, “All who take the sword will perish by the sword” (Matt. 26:52). And ultimately, of course, Jesus himself freely accepts his wrongful killing by political and religious authorities, never showing even a hint of physical resistance. What stronger argument for Christian nonviolence could there be?

On the other hand, the question of what it means to follow Jesus’ example in particular times and places and for those in particular social roles has never ceased to arouse debate among Christians. In the first two centuries after Jesus’ death, many of the most prominent voices in the church firmly condemned violence as sinful. Tertullian, for instance, who is sometimes called the “father of Latin Christianity,” argued that no form of killing was permitted to Christians, to the point of claiming that public office and military service—which in his day meant serving the Roman Empire—were usually incompatible with Christian discipleship.

Yet the church was scarcely of one mind during this period, nor were the proclamations of its writers always consistent with its practice. Despite the widespread belief that Christians were forbidden from joining the army, for example, active soldiers who converted to Christianity were usually welcomed to the faith and allowed to retain their roles. Likewise, there was quite a diversity of views on whether Christians could hold public office, as there was on the church’s relationship to the state more generally. The widely influential church father Origen of Alexandria held both that killing was wrong for Christians and that the use of violence by the Roman Empire was necessary to retain social order.

During the fourth century, as Christianity gradually ceased to be a persecuted minority religion and became instead the official religion of the Empire, the situation changed. Bishops and theologians could no longer debate whether Christians should serve in the military or hold public office: It was simply a fact that they did. And whereas before many church leaders had seen it as their calling to preserve the faith by resisting the Empire, most now came to regard it as their responsibility to guide it. The church was no longer a countercultural movement within a wider pluralistic society ruled by pagan emperors. It was the “spiritual power” charged with the pastoral care of all of society’s members, from the poor and marginalized to the emperor himself.

As the church’s role within society changed, its prevailing attitude toward violence did as well. Brilliant bishop-theologians such as Ambrose of Milan and Augustine—both close, in their lives, to the seat of imperial power—fashioned a new moral framework that would come to dominate the teaching and practice of the Western church for centuries. That framework continued to affirm nonviolence as the Christian ideal, binding especially upon clergy and religious and aspirational for all members of the faithful. At the same time, it also recognized that the ideal of nonviolence was not applicable to all Christians, specifically those in positions of public authority and responsibility: government officials, soldiers, law enforcers, and so on. For these people, recourse to violence was often sadly necessary to preserve order and constrain evildoers.

While thus allowing for violence, the Christian thinkers who established what came to be called the “just war” tradition were also highly concerned about regulating its use. Augustine, for example, strictly denied private citizens the right to kill, even in self-defense. Killing in self-defense, he argued, failed to reflect the sacrificial love of enemy commanded and embodied by Christ. Even for those holding formal public offices, violence was only licit if it conformed to strict moral criteria. Over the ensuing centuries, leading scholastic theologians such as Thomas Aquinas continued to refine these criteria. In the process, they helped to lay the groundwork for modern international law.

Until the 20th century, the just war tradition dominated Catholic thought and practice. It was not the only approach to violence within the church, however. Several religious orders that emerged during the Middle Ages, such as the Franciscans, made nonviolence foundational to their way of life. Nonetheless, the orders were commonly held to follow “counsels of perfection” not applicable to ordinary Christians.

By contrast, during the Protestant Reformation, a new stream of Western Christianity arose for which pacifism was the default option for all the faithful. At its core were the churches we now call “Anabaptist,” such as the Mennonites, Amish, and Brethren. While the so-called “magisterial” reformers such as Martin Luther and John Calvin continued to insist upon public officials’ right—and responsibility—to use violence, these more radical reformers sought to return to the more uncompromising nonviolence of the early church. Christ, their leading figures insisted, had never intended for his disciples to be the rulers or law enforcers of the world; indeed, it was precisely the holders of the sword who had executed him. Rather than conforming to the norms of a sinful world, Christians were called to stand apart from it, forming alternative communities and bearing witness to a fundamentally different way of life.

Since the Reformation, the Anabaptist traditions and later the Quakers—often referred to as the “historic peace churches”—have been the most ardent and unwavering defenders of Christian pacifism. Still, for centuries they remained a minority voice within global Christianity and often an actively marginalized one. It was only the distinctive horrors of 19th-century warfare and the two world wars of the 20th century that drove many Christians from historically non-pacifist traditions to reconsider their views on violence.

Within Catholicism, that process arguably began in the 20th century. An early catalyst was Pope Benedict XV. While not strictly a pacifist, this largely forgotten pope dedicated most of his energy to promoting world peace during and after World War I. In the following three decades, a powerful peace movement began to coalesce within the church itself, led by movements such as the Catholic Worker (founded in the United States in 1933) and Pax Christi International (founded in France in 1945). Until the Second Vatican Council, however, official Catholic teaching continued to insist upon citizens’ responsibility to defend their states when necessary. General conscientious objection, Pope Pius XII averred, was not a permissible option for Catholics.

This changed at Vatican II, when the assembled council members offered a “fresh appraisal of war.” Emphasizing the unprecedented destructiveness of modern warfare, they not only granted the legitimacy of conscientious objection, but also recognized Christian pacifism as a valuable complement to the just war tradition. In positioning the dignity of the human person at the heart of Catholic teaching, Vatican II also articulated a new rationale for nonviolence. Violence itself, the council members emphasized, is all too often the result of entrenched social injustices: of society’s failure, that is, to respect human dignity.

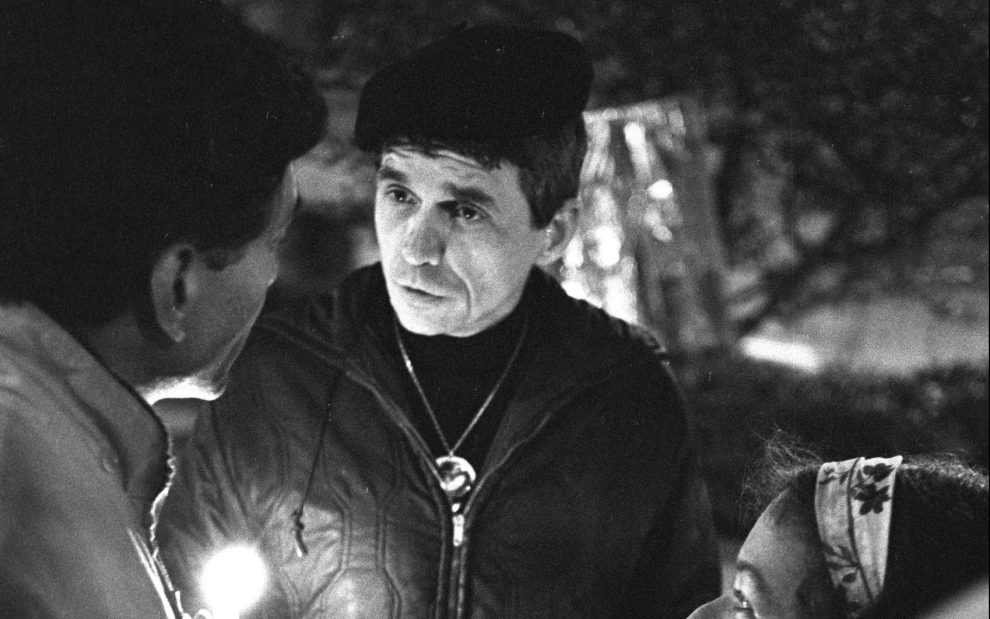

Since Vatican II, the church has moved progressively toward an embrace of nonviolence in practice and in doctrine. At the level of practice, the post-conciliar period has seen a proliferation of Catholic peace initiatives. Ranging from the anti-war protests associated with the Berrigan brothers in the United States to the global peace negotiating efforts of Sant’Egidio, these initiatives differ in their priorities, strategies, and charisms. All nonetheless share a bedrock commitment to nonviolence as a fundamental element of Christian discipleship. Many also draw inspiration from 20th-century movement leaders such as Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr., who have shown how nonviolent resistance can be a highly effective method for social change.

Meanwhile, Catholic doctrine and theology have followed a parallel course. While the post-Vatican II popes from Paul VI to Francis have continued to uphold the just war tradition, they have applied its criteria increasingly stringently, leaving it debatable whether any recent wars have been in fact just. Simultaneously, through their social teaching these popes have emphasized peace as an integral aspect of social justice, which is best—and perhaps only—advanced through nonviolent methods. Hence Pope Francis’ call in 2016 for a “politics of nonviolence,” premised on building long-term peace through the peaceful promotion of social justice.

In the same year, some prominent Catholic peace activists and theologians associated with Pax Christi went even further. At a much-publicized conference, they contended that the church’s entire just war framework had become obsolete and that an alternative approach centered on “just peace” was necessary.

Although proposals like these remain highly disputed, they testify to the shift that has taken place within Catholicism and ecumenical Christianity more broadly. After centuries of relative marginalization, nonviolence has reemerged during the 20th and 21st centuries as a key plank of Christian discipleship.

One could argue that this development reflects a return of Christianity to its roots, a closer approximation of Christ’s own teaching and example. But whereas for the first Christians, nonviolence meant primarily the avoidance of violence, in its contemporary incarnation it has assumed a new form: the active promotion of peaceful and just society through nonviolent means. How might this recovery, and reinvention, of Christian nonviolence shape the church in the future? And what impact will it have on the world? It remains too soon to tell.

No comments:

Post a Comment