Give the Sacred Heart devotion a second chance

The

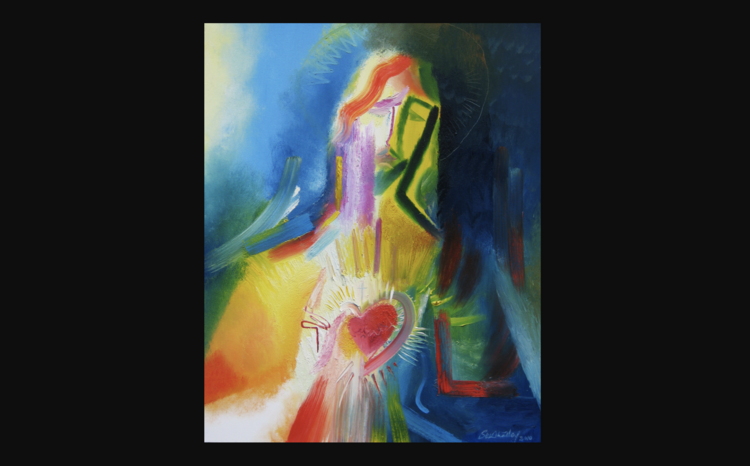

Sacred Heart of Jesus is depicted in a modern painting by Stephen B.

Whatley, an expressionist artist based in London. Wide devotion to the

Sacred Heart of Jesus began after the private revelations of a French

nun, St. Margaret Mary Alacoque, between 1673 and 1675. A feast was

extended to the whole church in 1856 and is marked the Friday following

the feast of Corpus Christ. (CNS photo/Stephen B. Whatley)

The

Sacred Heart of Jesus is depicted in a modern painting by Stephen B.

Whatley, an expressionist artist based in London. Wide devotion to the

Sacred Heart of Jesus began after the private revelations of a French

nun, St. Margaret Mary Alacoque, between 1673 and 1675. A feast was

extended to the whole church in 1856 and is marked the Friday following

the feast of Corpus Christ. (CNS photo/Stephen B. Whatley)If

you read enough novels that feature Catholic characters, you’re bound

to run across a Catholic family described as having an “oleograph of the

Sacred Heart” hanging somewhere in their house (usually the kitchen,

the dining room or the bedroom). It’s the lazy novelist’s shorthand for a

certain kind of kitschy, overheated devotional stance that is supposed

to “locate” for the reader the pious sensibilities of the (usually

indigent or uneducated) Catholic characters.

The Sacred Heart is one of the few devotions that have probably suffered from its artistic representations. Many of the images with which older Catholics are familiar are both kitschy and off-putting: a doe-eyed Jesus pointing to his heart, which is always pictured outside his body. There is the yuck factor (the bleeding heart surrounded by a crown of thorns is often pictured in gruesome detail) and the disbelief factor (there's no way that a carpenter from Nazareth looked so effeminate). It’s a tragedy that art has distanced many Catholics from a powerful way of looking at Jesus.

The Sacred Heart is one of the few devotions that have probably suffered from its artistic representations.

The devotion began with the mystical visions of Jesus and his Sacred Heart as revealed to St. Margaret Mary Alacoque (1647-1690), a Visitation Sister living in the French town of Paray-le-Monial. As is often the case, the sisters in her community were highly doubtful about her reported visions. At one point Margaret Mary was told in prayer that God would send her “his faithful servant and perfect friend.” Shortly afterwards, the mild-mannered St. Claude la Colombiere, a Jesuit priest living nearby, was assigned to serve as her spiritual director. Later, Margaret Mary would have a vision that showed their two hearts (hers and Claude’s) united with the heart of Jesus.

From that point the two worked together to spread the devotion, which became strongly associated with the Jesuits, who promoted it with vigor in the following centuries. As the devotion flourished, the paintings, mosaics, sculptures and yes, oleographs proliferated. So did parishes, hospitals, retreat centers, schools and universities named in its honor. Everything you know that is named “Sacred Heart” (including the great church of Sacré Coeur in Paris) stems from these two people—and Jesus of course.

(By the way, Fr. Claude wasn’t thought of too highly by his brothers either. Jesuit communities used to have house “historian” who would record the events of the community life. The final few days before Claude’s death were recorded as follows by the house historian: “Nothing worthy of note.”)

The Sacred Heart is nothing less than an image of the way that Jesus loves us: fully, lavishly, radically, completely, sacrificially.

In time, though, devotion to the Sacred Heart fell off to such an extent that Pedro Arrupe, SJ, then the superior general of the Society of Jesus, had to remind his brother Jesuits in 1981: “I have always been convinced that what we call ‘Devotion to the Sacred Heart’ is a symbolic expression of the very basis of the Ignatian spirit.” He told them that the Sacred Heart is "one of the deepest sources of vitality for [my] interior life." Yet Father Arrupe acknowledged, "In recent years the very expression ‘Sacred Heart’ has constantly aroused, from some quarters, emotional, almost allergic reactions."

Those “allergic reactions” mean that we are missing a powerful and vivid symbol of the love of Jesus. For the Sacred Heart is nothing less than an image of the way that Jesus loves us: fully, lavishly, radically, completely, sacrificially. The Sacred Heart invites to meditate on some of the most important questions in the spiritual life: In what ways did Jesus love his disciples and friends? How did he love strangers and outcasts? How was he able to love his enemies? How did he show his love for humanity? What would it mean to love like Jesus did? What would it mean for me to have a heart like his? How can my heart become more "sacred"? For in the end, the Sacred Heart is about understanding Jesus’s love for us and inviting us to love others as Jesus did.

Perhaps newer images are needed to revive

this storied devotion (like the one above, by Stephen B Whatley, an

expressionist artist based in London). Or perhaps we just need newer

ways of thinking about this Solemnity, which is today.

Last year I participated in the “Hearts on Fire”

retreat, a young-adult retreat sponsored by the Apostleship of

Prayer. It was a wonderful day-and-a-half of talks and prayers and songs

and sharing led by a group of talented young Jesuits. (This summer

Hearts on Fire is making its tour of the South.) During one session,

Phil Hurley, S.J., the director of the program, gave a lively

presentation to the young adults on the Sacred Heart. He recounted how

he had recently shown some images of the Sacred Heart to some

schoolchildren. “Why do you think Jesus’s heart is shown on the outside

of his body?” he asked the children.

One girl spoke up: “Because he loves us so much that he can’t keep it in!”

"This essay is excerpted from 'Awake My Soul: Contemporary Catholics on Traditional Devotions,' edited by James Martin, SJ."

[Editors’ note June 28, 2019: The photo (and the in-article reference to it) used for this article has been updated]

No comments:

Post a Comment