I was at the first Earth Day. And I carry what I learned about care for creation to this day.

The first Earth Day, over 50 years ago, was, to a 9-year-old, pretty groovy. In 1970, Americans hadn’t heard the term “climate change,” today a hotly contested political football, but were—this will seem hard to believe—nearly united in their desire for “conservation.”

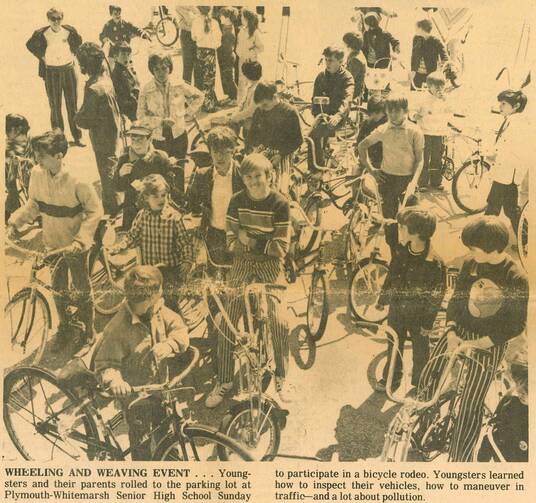

The first Earth Day, a loosely organized grassroots movement, aligned people of all political stripes and cultural backgrounds, something that news reports of the day confirm. As a kid, it seemed obvious: Who wouldn’t want to conserve the environment, stop air pollution and help living things flourish? The first Earth Day was celebrated in my hometown with a big outdoor fair at a local park. The next year, the local newspaper, dated April 19, 1971, proclaimed “Bike-In Heralds Earth Week.” I was part of that Bike-In, at our local high school, sucking on a popsicle in the accompanying photo of happy kids on their Sting-Ray bikes, under the pull quote “130 Leave Their Cars Home.” The catchy lede to the story in the Today’s Post, a now-defunct daily newspaper in the Philadelphia suburbs, quoted a 5-year-old girl who scolded the reporter for driving a car to the Bike-In.

“Don’t you know cars pollute the air?” she said. “That’s what this is all about.”

It certainly was obvious to me, someone who enjoyed nature, who loved traipsing the woods across the street from our house and biking through a meadow filled with wild snapdragons and daisies. I saw, and still see, conservation as a beautiful thing.

Other Earth Week activities were highlighted on the front page, showing what a big deal it all was. On “Earth Monday” the dedication of a new glass recycling center would happen at 1 p.m., and on Earth Tuesday, a letter-writing initiative would be organized by the League of Women Voters, hardly a radical group then or now. It was, to be sure, a simpler time, with a great deal more unity. By the end of 1970, the Environmental Protection Act had been passed under a Republican president, Richard Nixon. Few politicians opposed it, and even if some did, it wasn’t something that people would come to blows over. The importance of conservation seemed, in a word, obvious. So did the newer word we were hearing about: ecology.

It certainly was obvious to me, someone who enjoyed nature, who loved traipsing the woods across the street from our house and biking through a meadow filled with wild snapdragons and daisies on the way to elementary school on warm spring days. I saw, and still see, conservation as a beautiful thing.

In the early 1960s, I marched around with a dozen or so kids on my street picketing a local highway nicknamed the “Blue Route,” for the blue line that had appeared on a city planner’s map decades before. A local cause célèbre, it was destined to slice through our neighborhood and destroy a fair portion of the woods that I enjoyed so much. We had, as I recall, seen the kids on “The Brady Bunch” picketing, and that was good enough for us. So we picketed our neighborhood. I’m not sure what good it did, since there weren’t any city planners living nearby, but we did it anyway. It seemed, again, obvious.

In the end, the Blue Route was built (it’s now I-476). Whenever I drive on it and marvel at the time saved in getting from one town to another, I ruefully remember our picketing. And it did destroy much of those woods.

Who wouldn’t want to save the tiny and vulnerable daphnia and volvox who lived in our neighborhood?

Where did kids get this interest? As I had mentioned, this was a non-partisan issue, so all our parents taught us, supported us and encouraged us. And how could you not trust your parents? A few years later, the nation’s concern would turn to the ozone layer, which, we were told, was being destroyed by fluorocarbons, the kinds of things that many of our moms used in their hairsprays. It was in the 1970s that manufacturers started switching to pump sprays, and the ozone was indeed saved, or at least mended.

But it was also something taught in school. It was simply understood as the best science of the day, and so taught by our science teachers, willingly and with a sense of responsibility. One day, our fifth-grade class was asked to visit a nearby stream (a ditch, really) and draw water from it. A few hours later, under a microscope, we peered at all the little creatures floating around in it. “Imagine what pollution does to them!” said our teacher. Who wouldn’t want to save the tiny and vulnerable daphnia and volvox who lived in our neighborhood?

One of the most popular books in Ridge Park Elementary School was a book by the science writer Rachel Carson. It was a “Young Readers” version of her book The Sea Around Us. I kept my copy for many years, poring over its descriptions and photos of ocean life, of which I knew little.

It was of course Ms. Carson and her book Silent Spring (which we would read in junior high school) that presaged the modern ecological movement, with its cri de coeur against the effects of DDT. (The perfectly chosen title is her image of a bird-song-less springtime.) Just recently, I read William Souder’s magnificent biography of this now-personal hero, who not only fought cancer as she put the final touches on her masterpiece but was also a member of the L.G.B.T.Q. community.

No comments:

Post a Comment