Women in the Church - so tired of waiting

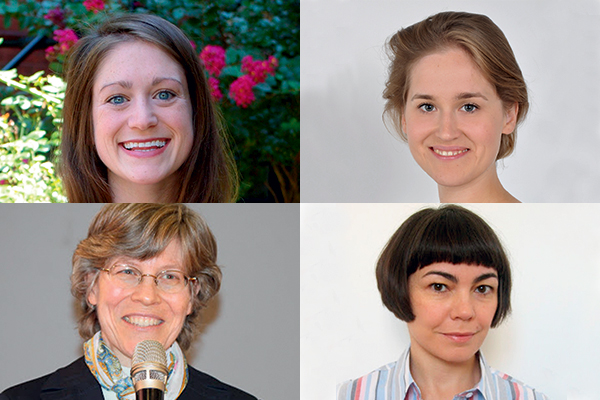

Clockwise, from top left: Kate McElwee, Zuzanna Flisowska, Gudrun Sailer and Sr Bernadette Reis

Since his election, the Pope has made noises about wanting to see a greater role for women in the Church. But for many of those hoping for change, this papacy has so far proved a bitter disappointment, with Francis talking the talk but failing to walk the walk

The year is 2025, or perhaps it’s 2030. Francis is gone; we have a

new pope and, like all leaders, he must decide on the priorities that

will dominate his time in office. Across hundreds of years and hundreds

of popes, there have been many priorities. But one agenda has never been

top of the pile for any pontiff. Sadly, it is an agenda that could

perhaps have changed the terrible trajectory of the Church’s path in

recent years, stemmed the avalanche of decline in its credibility, and

circumvented the increasing perception of it as an obsolete curiosity

rather than a radical voice in a fast-moving world. That agenda is

women. If a pope had made it a priority, things might now look very

different.

The Catholic Church is a masterclass in patriarchy.

Power is concentrated overwhelmingly in the hands of male clerics. In a

touch of sheer genius, women were given status – the semblance of

reverence on the pedestal of Mary – but almost completely barred from

decision-making or authority. Through history, of course, countless

women have found a way round Rome’s rules – think the

seventeenth-century Mexican nun Juana Inés de la Cruz, who championed

education for women and was ostracised by the bishops; or the English

reformer Mary Ward, whose same idea a few years earlier had met with the

same sort of reception. Mary Ward was declared Venerable in 2009; the

Church has a track record in posthumously “sanitising” its radical

women, or reframing them in a way that suits its own narrative: Mary

Magdalene was far too powerful as Christ’s wealthy patron and right-hand

woman (the true story) but as a reformed sex worker forever regretting

her “sins” (the rewrite) she fitted the bill perfectly.

In Rome, where I was just before its lockdown, the women who work for something better seemed weary, some of them almost dejected. One day, like Mary Ward, these women will be seen as warriors of much-needed reform; but for now they are sidelined and their cause is belittled. “It’s very lonely doing this work, in this place, at this time. There certainly aren’t a lot of supporters for us in Rome,” says Kate McElwee, executive director of Women’s Ordination. A photo on its website of its inaugural conference shows a large room packed with women, nuns included, and men, priests included, who believed the time for change was nigh. The year was 1975 and the scent of revolution was in the air. Forty-five years later, hopes have been raised and dashed one too many times.

McElwee and I meet for lunch in a bustling eaterie near the Piazza

del Popolo in the week after Pope Francis has released Querida Amazonia.

Hopes had been high that, at long last, this could be the start of a

process that would see women ordained as deacons (and married men as

priests): the Synod of the Amazon’s final document had called for both.

But just as with the report of a working group Francis had set up to

look at the question of women deacons, the debate was stalled. As so

often with Francis, the language was vague and open-ended; it was a

field day for Vatican-watchers, but a depressing downer for women like

McElwee. It “feels like a breaking point”, she told me sadly.

Francis,

she said, had been “stirring the pot” – apparently open to the idea of

women’s ordination to the diaconate. But for all his emphasis on the

importance of listening, at the point where leadership matters –

decision time, the crunch point – he had once again edged back from

taking a leap of faith. “All this lip service after several years is

difficult to reconcile with your faith,” said McElwee, as we chatted

over pizza. “We know women who are being called to be priests – the

Church has lost two generations of educated women.” Others might argue

it has lost hundreds of generations.

Look on the websites of the

Church’s feminist organisations (Women’s Ordination Worldwide, Voices

of Faith, Catholic Women’s Council, Roman Catholic Womenpriests – and

there are many more) and there they all are in the photographs, the

women who could today be among the Church’s leaders, and instead are its

marginalised campaigners. Adding to their frustration is the Church’s

constant narrative of a “vocations crisis”. “Some of these women have

been waiting for decades – they are great witnesses to faith,” says

McElwee. “There’s a huge influx of women doing theology degrees – but

what career paths are open for them?”

Another day, another

disillusioned campaigner. I am in the Tiber-bankside office of Voices of

Faith, meeting with its general manager Zuzanna Flisowska. “Either the

Pope doesn’t see it, or he just doesn’t have the energy for the

earthquake we need where women are concerned,” she tells me. “What he

says [in Querida Amazonia] about ecology and migrants is wonderful – but

in the paragraphs about women he just repeats things he’s said already.

Women here in Rome are tired; nothing is changing. I know theologians

who are saying, We’ve waited 40 years – it’s all exactly the same.”

Flisowska

does give Francis credit for opening up discussion about equality for

women, after it was shut down by John Paul. “He did open up the

dialogue,” she says. “He did encourage us.” Indeed, time and again,

women pressing for change would tell me how buoyed up they had been by

Francis, before being infuriated by his failure to act. There’s a sense

among many that he’s playing with it as a topic, and annoyance that he’s

using it as a fob. At the beginning of this year, he said women “should

be fully involved in decision-making processes” in the Church. They

should have more than merely a “functional” role, he said last November;

as early as 2015, he was making noises about wanting to see a “greater

role” for women in the Church, and calling the gender pay gap a “pure

scandal”.

“We want Francis to put his money where his mouth is,” says Sr

Bernadette Reis, who works in Vatican communications. “I believe women

need to be present at the decision-making level in the Church as Francis

is suggesting they should.” Like the other women I’ve spoken to, she’s

grateful to him for allowing the debate. “At least the Pope is raising

the questions – that’s a big step forward. The question for me is: among

the successors of Peter, where are the successors of Mary?”

Sr

Bernadette is not a radical; nor is Gudrun Sailer, editor of the German

service of Vatican Radio. We have a coffee together on the sunny balcony

at the station’s headquarters overlooking the Castel Sant’Angelo.

“Francis said he was unhappy at the way women were treated, that he

wanted to see change,” she says. But he has failed to deliver: and it’s

not only the campaigners he’s disappointed, it’s mainstream Catholic

women who are acutely aware of the growing gulf between the lack of

opportunities for women as leaders in the Church and the growing

opportunities for them in every other area of their lives.

Over

another coffee, I meet a woman who’s employed at the Vatican – more than

one in five Vatican employees are female, most of them in lower-rung

jobs. She wants to remain anonymous: the Pope, after all, is her boss,

and she feels he’s doing nothing like enough on the woman front.

“It’s men who have his ear the whole time – working here, you really notice that,” she tells me. “In many ways, Francis seems to have gone backwards on women. You feel he’s looking for ways to appear to be doing something for the women’s cause, while not really engaging with it at all. So yes, there have been a few high-level appointments of women – Barbara Jatta has become the head of the Vatican Museums, and Francesca Di Giovanni is undersecretary of the Vatican’s secretariat of state – but really, they’re anomalies. You have to look at the culture here, and you have to look at the figures overall. Women are not in powerful positions in sizeable numbers – and for the Church, in 2020, that really matters.”

Francis has just appointed six women to the Vatican’s Council for the

Economy: it has 15 members, and previously they were all male. In

April, he set up a second commission to study the question of whether

women could be ordained as deacons. The women I met in Rome point out

that he has made appointments before; what is needed is systemic change

rather than the promotion of a handful of highly visible women. For many

campaigners, Francis is good at talking the talk, but fails when it

comes to walking the walk –at a time when action has never been more

crucial.

But there’s a glimmer of hope from a dark corner.

According to Zuzanna Flisowska, the abuse crisis has fundamentally

changed the way Catholics think about power and the hierarchy. “There’s a

sense of, ‘enough!’” she tells me. But as with all the work around

abuse, reform only happens when those pressing for change are seen as

allies rather than irritants by insiders – and when it comes to

feminists and the Vatican, that’s still a work in progress.

Some

believe, too, that the pandemic could bring positive change. “It’s

changed Catholic practice, and made space for more creativity,” says

Kate McElwee. “There’s been a growth in women-led liturgies online, and

in many ways the women who are part of our movement were in a very good

place to adapt to the new ways of worship. It’s an affirmation for what

we’ve always been about, which is the Church beyond its walls.”

Against

the odds, McElwee remains optimistic. “I think it’s all going to feel

as though it’s impossible, and then overnight it will just happen,” she

says. “Catholic women are so strong. We will find a way.”

Joanna Moorhead is arts editor of The Tablet.

No comments:

Post a Comment