An atheist’s return to the Catholic Church: a story of death, love and meaning

I graduated from high school in Colorado in 1999—the final year of the millennium and nearly 2,000 years after the birth of Christ. In April of that same year, just an hour down the road, two students by the names of Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold precipitated the era of nihilistic, obliterative massacres in America, murdering 12 classmates and one teacher at their high school in Littleton, Colo., before killing themselves.

This was before “mass shootings” had been put on a seemingly endless loop. The entire country had not yet learned the unspoken, dark habit of being unsurprised. Those of us who were set to graduate that year discovered that some of our generation believed it was better to destroy than to create, better to nullify than to affirm. Rather than a journey toward graduation together, these two boy-men had chosen death. Nulla cum laude.

Fyodor Dostoevsky had prophetically warned in Demons—I wonder if it was on the shelf in the library that day at that school—that the deadliest poison in human life is not anger but boredom. A boredom that contains the most thorough rejection of existence. A mocking, lazy, listless, proud, ugly and spiteful boredom that looks at the whole of being, its shimmering grandeur, its never-spent newness, and says a single word: no.

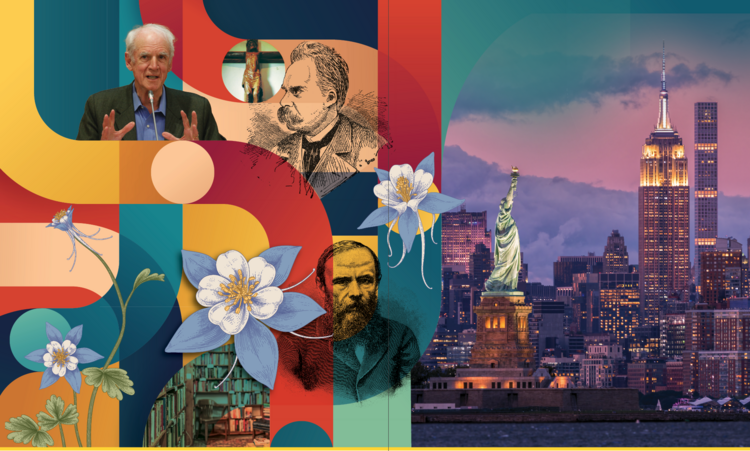

The high school where the massacre happened was named for Colorado’s official wildflower, the columbine. In the Rocky Mountains, columbines grow in alpine meadows and tundra. Their fragile blooms gather in clusters, ghostlike amid the jagged rocks, the remote peaks and dark ravines, a luminous and strange apparition of the gift of being.

I remember traveling to Columbine at least one time before the shooting, with my junior varsity soccer team to play a scrimmage. What struck me about the building was that it resembled our own. Elements repeated, as if by a copy-and-paste function: hard lines, panoptic arrangements, naked glass, and unadorned bricks and concrete. A bad infinity, without redemption. A combination of the hard boundedness of matter and the empty eternity of mathematical form.

Similarly, my hometown was sprawling to the south, away from its historical core and into an ever-repeating suburb. Tracts of anywhere-and-anyone housing, alternating the same chain stores with the same slick advertising. “Little boxes” as Pete Seeger had sung, “little boxes made of ticky tacky.” Blotting out the mountains, the columbines, the planets, the wind over the plains and the stars. As much as we despised Klebold and Harris for what they had done, some of us silently wondered: Was a different form of the same unholy poison inside of us, running through our veins? Had we been born into what Bob Dylan referred to in “Desolation Row” as the “sin” of “lifelessness”?

Many experienced it as an overwhelming desire to escape or move elsewhere. Arcade Fire summarized the feeling in a later song titled “The Suburbs”:

In the suburbs I

I learned to drive

And you told me we’d never survive

Grab your mother’s keys we’re leaving.

Two atheisms

My earliest atheism was not one of conviction. That would come later. Rather, it was one of habit—a pattern of life, a disenchanted way of being in the world and perceiving reality. The feeling of an absence.

Although my father could be a fierce critic of organized religion (particularly Christianity), he was also no atheist. He taught me to see in nature a deep spiritual dimension while hiking in the mountains, and also to admire the artistic searching of the counterculture. My mother was a practicing Catholic but was mostly silent about her own faith. From before I can remember, I inherited my father’s skepticism toward churches. If anything, I was far more skeptical than he was of nearly all spiritualisms, which I saw as bogus—from Christian evangelicals to New Age hippies.

I perceived many of the Christians around me as less alive than the secular progressives I knew (and in my teens I counted myself as one) to human loss and suffering. Less responsive to injustice. More acclimated to evil and to the deadening boredom.

Their faith and my disbelief seemed to not make a jot of difference (although I might have reflected longer on my mother and what Greg Boyle, S.J., once called the “no-matter-whatness” of love). At the time, however, it seemed clear that at least unbelief had the advantage of looking at reality without any wild metaphysical conjectures or unnecessary add-ons. This initial “felt” atheism (as the writer Joseph Minich calls it) was not very militant—it was even somewhat apathetic—but it would later turn into a second kind of atheism that was far more intensely held and philosophically sophisticated: an atheism of conviction.

Holiness of the flesh

Have I not mentioned Lindsay yet? I met her in the fall of my senior year of high school. She edited the stories I submitted to the student newspaper. She was bright and sensitive and absolutely entrancing. She was also there before the news of the mass killing. A gift on the rocky trails of life. A columbine flower.

Beginning in 1998, when we met and started our long, sprawling conversations, Lindsay and I both wanted out of this deadening feeling—which we associated chiefly (and not completely fairly) with our hometown. One early method of escape was each other. A quickening of the heart. A newness of life. There is no emotional landscape quite like that of young people infatuated or in love. You can look at each other’s faces for hours.

After what seemed to me like very long months of ritual kissing, I lost any bona fide claim to chastity on Easter Vigil. I had been catechized enough to be haunted by the liturgical calendar. Lindsay did not know. She grew up in a culturally Protestant family that had long ago disgorged itself from all religion.

It must have been about two years earlier that I attended my final Mass. From early childhood, my mother insisted we go to Sunday Mass and receive the sacraments. But the sacrament of confirmation marked the last time I went to weekly Mass for well over a decade. The irony of this—like my new profane sacrament of the erotic—was not lost on me at the time. My adult confirmation of faith was in actuality my public ceremony of departure. I had my own holy Mass now and my own holy Communion. It seemed far more bodily than any paper-thin wafer rationed out by priests.

Besides, graduation meant I was leaving. From Colorado. From my mother’s Mass-going. From the infinite, repeating, morbid liturgy of the suburbs. I was leaving for New York. Lindsay was leaving for Kansas and later Boston. We were staying together. We would write letters. I wrote poems. We would do everything to visit each other. If I had been asked at age 18, “What do you have faith in?”, I would not have hesitated to answer (and it was not such a bad answer after all): “I have faith…in Lindsay.”

Atheist hero

As an undergraduate studying politics and philosophy at Vassar College in the Hudson Valley of New York, I became convinced that the only rational view of existence was that it was absurd. I read Camus, Sartre, Kafka, Kierkegaard and many others. But most of all I read Nietzsche and Heidegger. I remember many slow hours in Vassar’s beautiful neo-Gothic library, bent over Heidegger’s Being and Time to learn that death is “always my own.” The authenticity of real thinking could make us aware of what we already are.

This is when the void first became palpably, even terrifyingly real to me. It became realer to me than any existent thing. Existing things were hardly here, after all, only skating for a while on the surface of the void before they vanished. But now, an emptiness was opening up before my field of perception. It was so vast and so awe-inspiring that it perhaps even heralded, without my knowing it, a mystery no mind can comprehend. If an atheist can feel the fear of God and not know it, I think this experience might have been it.

The professor who had the greatest influence on me during this time was a philosopher who offered classes in phenomenology and existentialism. She taught me that philosophy must start from existence, from the actual embodied reality of life, not from the abstractions that preoccupied so much of academic philosophy and the modern world. Academic philosophers, for instance, locked themselves inside the nutshell of all sorts of pseudo-problems, from Zeno’s Paradox to Descartes’s “cogito ergo sum.” But existential philosophy went back to the reality of being in the world, which always precedes knowing.

She also offered a kind of solidarity before the absurd. She could quote Nietzsche’s aphorisms the way some Christians can quote Scripture. One time, she told me that most of humanity was psychologically or even spiritually hemophiliac: A single cut and they would bleed to death, so they buffered themselves from existence. Turned away from the void.

But atheists were different. Atheists had intellectual courage and spiritual strength. They could survive more truth than others could. The 17th-century French writer François de La Rochefoucauld had said neither death nor the sun can be looked at for very long. This is true, but the atheist could look at the terrifying sun the longest. Atheist in this way became a badge of honor for me. It was the name for a new heroism.

Those who have never been atheists must know: Everything in life can come to signify the death of God. That can include family, relationships, science, politics, technology, psychology, nature, one’s own conscience. Everything can witness to the void and pay homage to it. As Nietzsche declared in The Genealogy of Morals: “Unconditional honest atheism…is the only air we breathe, we more spiritual men of this age!”

At this time, Lindsay transferred to Boston College. We only noticed much later how the Jesuits there began to influence her. They were having her read not only Nietzsche’s Birth of Tragedy but also T. S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” and John’s Gospel. Once a semester, with a borrowed car, she visited Vassar College. We never gave up on each other or the relationship. I thought myself alone, but I was already in relationship with someone and something I did not fully fathom.

A hell of a time

After graduating from Vassar, I followed Lindsay north to Boston, then sometime later we moved to New York. At that time, I thought of New York not only as the hub of American culture but as the capital of the times. The metropolis of the epoch. Living in “The City” (everyone referred to it this way grammatically—with the definite article, as if there were really only one) excited my pride. After growing up in a small town in Colorado, simply surviving in “The City” seemed a grand accomplishment. I decided to become a novelist and poet. For who more than artists created their own meanings ex nihilo, as a rebellion against the void? Art would be my great “amen” of the creative will to the emptiness of a world without God. We made our meanings. We would make our own gods.

I carried out this project for several years. By day, I worked at a branch of the Strand bookstore near Wall Street that later closed, called The Annex. When I arrived, some of the staff claimed dust from the 9/11 destruction of the World Trade Center towers still remained on the high shelves and hard-to-reach places. I mostly checked in new stock and shelved books in the narrow aisles. At night I wrote short stories, poems and novels.

I would also read more books than I could remember (everything from Joyce and Elizabeth Bishop to William Shirer’s Rise and Fall of the Third Reich and Julio Cortázar) until my mind and body gave out in the early hours of the morning. In the background the mercurial lyrics of Bob Dylan’s “Visions of Johanna” were often playing:

Little boy lost

he takes himself so seriously

He brags of misery

he likes to live dangerously.

This was around the time my body began to falter. I began to experience a swarm of symptoms—headaches, dizzy spells, numbing and buzzing in my arms and legs, extreme exhaustion—all of which I logged in a meticulous journal. By all appearances, I was a healthy young man, and yet my head would not stop spinning.

Finally, one night in October of 2005, I asked Lindsay to walk with me to the emergency room at the old St. Vincent’s Hospital off of Seventh Avenue in Greenwich Village. My heart was palpitating and I felt dizzy. I was certain I was dying. I remember staring at the dirty fluorescent ceiling in the emergency room while Lindsay held my hand with a look of pity on her face. Whenever one of the nurses or doctors passed by, she squeezed my hand and looked up earnestly, hoping they might at least pause to ask my name and why I was there. I was discharged in the morning—directed to see a number of specialists.

For reasons I could not explain, I felt like I was failing, but I did not even know at what. If life was about resoluteness before the void—the big nothing—then what kept anything from slipping into it? A few weeks later, the dizzy spells started again. My body was numb. It seemed almost as if I lacked the will to live.

The thread

This is what all my philosophy had brought me: I had no sense of what a good life was other than the struggle of my will against the void. And death—although I contemplated it constantly—was almost unthinkable. As conceited and silly as it sounds, if the sole meaning of the universe was whatever I projected outward, then if I died, everything meaningful died with me. Was this terrifying, vast emptiness also preparing a space? Even then was the hand of the divine digging in the soil, seemingly emptying me out, to later place a seed?

Over the course of several long months, I began to realize I was not sick in the medical sense at all. I was experiencing a collapse of meaning—not just spiritually but in my body. Lindsay was with me the entire time and I gradually began to return to health. One night, lying deflated in my sickbed in the West Village, I asked if she’d marry me. It surprised her. I had always said marriage was an inauthentic convention of the bourgeois class. It was like Pete Seeger’s little boxes—only imposed on human eros. Marriage was the realm of anonymous anybodies.

But suffering in that way—and Lindsay’s witness—had finally begun to teach me something different. Was there anything more beautiful than to promise to accompany someone to the vanishing point on the horizon of existence? No matter what? Although we were not yet married, was not this accompaniment what Lindsay was already doing for me?

I wanted to say a full, happy and eternal “yes” to this love she was already showing me. I was not able to say it anywhere near this way at the time. To the contrary, my proposal was muttered and half-stammered: “Would you marry me?” Or maybe: “I think we could maybe get married?” But it also brought sparkling tears to pretty Lindsay’s dark eyes because it was spoken in truth. She asked me: “Do you mean it?” “Yes, I mean it,” I repeated. “I mean it. Yes.”

Here was a love I did not deserve. It almost defied belief that she would still feel so moved to marry me—after all my selfishness and sickness, my arrogance and pride. Slowly I realized that even though I thought I had been living a heroic life in the face of a meaningless universe in which the only meaning came from me, I had in fact been surviving on a meaning that came from outside myself. I had always lived off of love—a dog eating scraps from the master’s table—but I had not fully put myself in love’s service.

Following Lindsay, I began taking small steps out of that dark corner. We married the next summer and moved to Chicago, where Lindsay attended graduate school in journalism and I worked for half a year in the basement of a bookstore near the Loop. But by the next year it was off to Berkeley for me, to study political philosophy and to begin a new life.

The strangeness of the self

At UC Berkeley, I went deep into the study of politics and the human sciences. My intellectual convictions had been longstanding when it came to the social sciences: I was dissatisfied. The social scientists kept building self-refuting theories—a long chain of sciences of human behavior that all assumed a mechanistic and impersonally causal science of human life was at hand. But a self is not reducible to a bundle of mechanisms. It is a living set of meanings. The narrative and literary artists I admired were worlds ahead of the psychologists and social scientists on that point. We are storytelling animals already living inside our stories—not stories that we command autonomously, but that we already find in midpoint in our families, cities, societies and worlds.

I still believe one of the best reasons to be an atheist would be if we could give an account of reality that eliminated meanings and revealed nothing but impersonal mechanisms. If the universe could be explained in terms of a naturalistic, immanent determinism, then atheism would be far more credible philosophically than theism. But here’s the rub: No one has actually accomplished this naturalist project. No one has even come close. It’s just a wild aspiration, an article of faith that disavows itself as faith. Instead, the actual human situation up to the present day is that meanings and stories cannot be eliminated from the world. Human existence does not seem to permit the subtraction or elimination of stories and meanings.

This is one way to understand how the self became strange to me again. No one was more definitive to me intellectually in this regard than the Catholic philosopher Charles Taylor. Before I read Taylor, I believed that no intellectually honest Christian faith was possible. Among my favorite quotes to repeat as an atheist was Nietzsche’s barb from The Genealogy of Morals that “‘thou shalt not lie’ killed God.” But reading Taylor’s philosophy, and particularly his book A Secular Age, exploded forever my foolish prejudice that theists could not be intellectually honest.

The whole human world and cosmos became enchanted to me again. The only ultimately serious philosophical question is not suicide, as Camus thought, but instead: Which story makes the most sense out of our lives? The question is not: “Why is the universe meaningless?” Instead, it is: “Why is the world so tantalizingly and perplexingly overflowing with meaning?” Run to the furthest corner of the cosmos! You cannot escape…your story!

St. Mary Magdalen, Berkeley

On campus, I was in dialogue with a fascinating array of conflicting thinkers. At the same time, away from the university, in our tree-ringed Berkeley apartment, Lindsay and I were having rolling discussions about marriage, our love, what it meant to live well. Christ came up more and more often in these discussions. Not as some kind of moralism or dogma but as a beautiful person—as a person whose life resonated more and more as a story of what it meant to live well.

Christ seemed to be the first person in history who taught that the deepest and most fundamental meaning is love as sacrificial self-gift. Had we not been living that, even if only dimly before we even understood? Had Christ not been with us, not in our awareness, not in our cognition or comprehension, but in our unwillingness to give up on each other?

I began rereading Dostoevsky and the Gospels together and insisting that Christianity was the noblest story imaginable and that no human mind could have thought up something so beautiful. Christ’s biography in its four versions was absolutely shocking, baffling, unimaginably good. It took twists and turns no one could foresee. And inside the story were his stories. Strange parables about widows and mustard seeds, lost coins and lost sheep, wineskins and pearls, prodigal sons, rich men and servants.

The back-and-forth between us went on for a long time—perhaps longer than it should have. But at a certain point Lindsay became weary of all the talking. She began going to different churches by herself on Sunday mornings. She was of the absolute conviction that faith needed a relationship with something or even someone outside of oneself. You loved someone with your whole person, not just your mind. One day she suggested we go together to St. Mary Magdalen parish in Berkeley. I balked, but the thought stayed with me.

After a few weeks, I relented and we attended Mass together. I remember it being Lent and the earliest Sunday Mass—with many of the pews empty and the parishioners mostly white-haired. Late winter light was coming in through the windows and painting the pews, and a massive wooden crucifix on the wall, in liquid, pale white. In that light, Christ appeared both heavy in the hewn wood and to be levitating in frozen pain and serenity over his cross. It was as if he were only experiencing his agony for the first time that morning. Or maybe as if he had been experiencing that same agony every morning, since time out of mind.

Mass began. The priest processed in with an old woman holding up the liturgical book. The priest reached the altar, bowed his head, and turned around in his robes, speaking in what I later learned was an accent from Monaco: “In the name of the Father, and of the Son…” By surprise, something in my physical body remembered the old movements from childhood. My hand hovered as I mouthed the words without sound—as if I were just shaping them around a hollow object.

But as Mass continued, something strange happened. I heard words remembered from childhood, but fuller and more present (“I confess to almighty God, and to you my brothers and sisters…”). As when you see someone you once loved long ago but thought you would never meet again. In fact, you had given up (perhaps secretly without telling anyone) on loving them ever again. And when their face appears it is a full-blown ambush—a surprise sprung by reality itself—as the face both dearly familiar and somehow new fastens itself on your attention.

But this arresting feeling passed again, and my conversion was gradual over that year. I did not fall from St. Paul’s proverbial horse. My atheism had its rituals, too, that had saturated my bones and my mind. And sometimes when learning to pray again or to genuflect, my ego would float just outside my body like an apparition and whisper things to me. “Now is this not ridiculous?” I heard it say. “What are you bowing before? Fool! A big nothing!”

But for weeks that turned into months, I persisted, and the voice of the ego began to evaporate into silence. Little by little the attraction was becoming stronger than any sense of awkwardness or self-awareness. The Mass was seeping into my flesh and bones. The words were reattaching to my tongue (“God from God, light from light, true God from true God”). As Pascal had observed long before me: We often assume we need total understanding to have faith, but practice can precede belief. If you enter into relationship with God, faith will be mysteriously offered. You need only the humility to approach and ask.

Lindsay entered the church at St. Mary Magdalen on Easter Vigil in 2010. I followed her, because like so many times since we were teenagers, I wanted to stay close to her and see what she saw. For it is true as the Son of God said: “One does not live by bread alone, but by every word that proceeds from the mouth of God.”

No comments:

Post a Comment