How misogyny prevents many Catholics from accepting women in leadership

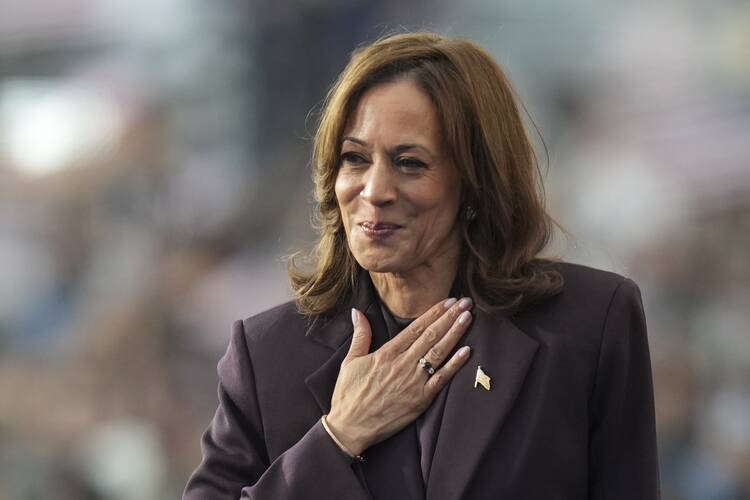

I didn’t cry until Vice President Kamala Harris turned from the podium where she offered her concession speech and began to walk away—steady in her stilettos, head held high. Her speech exuded the fruit of the Spirit: love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control. That is what a real leader looks like, I told my kids through tears.

But they already knew that. They have watched some of Donald J. Trump’s speeches (the rare segments that are appropriate for children), and their reactions have been disgust and confusion: “Why aren’t grown-ups standing up to that bully, Mom?”

I have the same question. Mr. Trump’s re-election may be called a great political “comeback” by pundits, but it is difficult for me to see anything but a bully who refused to concede his loss in 2020 and then sought to entrench his power through lies, misinformation and intimidation—and by attracting men who resist the autonomy of women. The news has moved on, but I am still processing.

Mr. Trump’s scandal-ridden first term (remember the kids in cages?) ended with his fomenting an insurrection on Jan. 6, and he has since been found liable for sexual assault and guilty of 34 felony charges. He built his campaign upon racist lies and xenophobic fear-mongering. He promises to fill nonpartisan government agencies with loyalists and to treat opponents as “enemies.” He has rejected the notion of human-caused climate change and promises to stymy efforts to help our planet flourish as our common home. Our children will suffer the result.

While some critics complained that Ms. Harris was too light on policy, a YouGov survey showed that most voters preferred her policies to Mr. Trump’s—if they didn’t know who proposed them. And to the degree that her opponent offered anything beyond “concepts of a plan,” most of his policy proposals, including mass deportations and ending efforts to fight climate change, are abjectly immoral.

We had the chance to say enough is enough, to reject chaos and division in favor of building an inclusive democracy. It is a fundamental Christian principle that all people are made in the image of God, so a campaign that traffics in violence, racism and misogyny should have been automatically rejected by Catholics. Yet a bit more than half of all voters ignored this evidence, and white Catholics were crucial to the Trump campaign’s success.

I will be honest: I believe that misogyny—conscious or not—motivated the silence and moral equivocation of many Catholic leaders, as well as the willingness of so many Catholics to disregard the common good in pursuit of political power. To the extent this is so, Catholic consciences are being malformed.

The roots of misogyny in the church

We can see the roots of this misogyny in some of the statements of our church fathers. Augustine, for example, blamed Eve for the fall of humanity, noting that the serpent targeted her because women are more easily deceived (i.e., less rational) than men. Thomas Aquinas, centuries later, called women “defective men,” and though there is some debate about his use of the term, it is clear that he held women as being subject to men because of inferior intelligence and “defective” because of their anatomy. In “Inter Insigniores,” a pronouncement from the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith in 1976, we read that women cannot be priests because “in such a case it would be difficult to see in the minister the image of Christ.”

Absent female authority in the church, and given this theological throughline, it is not surprising that female authority is so often feared or despised, and that many Catholic men (and women) consider it demeaning to follow the lead of a woman. Indeed, this is why misogyny is so insidious: Women who affirm the status quo tend to be amplified by male leaders in the church and in civil society, while those who question it are censured. (In the same way, pointing out misogyny is often derided as playing “identity politics,” but perpetuating the status quo of patriarchy is not.) And we know that associating women with “lower” faculties and seductive physicality has fostered the exploitation and domination of women for millennia—and this is tied to the exploitation and domination of the natural world, with which women have been identified. This association is even more pernicious for women of color.

We have seen the destruction wrought by this patriarchal mindset. By excluding women from leadership and systematizing power as domination, Catholics have fostered a paradigm that views the earth and those different from ourselves as resources to be plundered, rather than beings with gifts to share. This feeds the narrative that flourishing is a zero-sum game and the perception that the empowerment of historically marginalized people threatens the validity and meaning of those who have always held power—a key element of the disillusionment driving the MAGA movement to “take America back.”

I am heartbroken and angry that so many Catholics are perpetuating the patriarchal politics that has distorted so much of the Christian tradition. That Catholics bear so much responsibility for re-electing Mr. Trump, despite his moral depravity, is another moral failure of our church. Unless we learn from women—especially those on the margins—how to reimagine our faith tradition, we will continue to distort its beauty in ways that cause serious harm.

Candidly, I don’t know where this leaves me. As a woman, I often wonder how I can continue to identify with the church in this moment. But hope moves one foot in front of the other, and as Ms. Harris recognizes, is evident “in how we live our lives by treating one another with kindness and respect, by looking in the face of a stranger and seeing a neighbor, by always using our strength to lift people up, to fight for the dignity that all people deserve.”

In this moment of hurt and anger, I pray now for the grace to sit with the uncertainties, to stay near to myself in the love of God, and to not let the anger overcome my ability to love—though I affirm that anger can be a reflex of compassion. In this moment, I embrace and embody the witness of countless women who have gone before me, standing tall against the odds, testifying to the truth of our dignity and our right to participate fully and to lead in the church and the world. In this moment—despite the despair and chaos, when there are no adequate words to express the depths of my moral outrage—I lean into our God, who invites the world toward the wholeness of love.

Kathleen Bonnette works at the Center on Faith and Justice at Georgetown University, where she also teaches theology. She is the author of (R)evolutionary Hope: A Spirituality of Encounter and Engagement in an Evolving World (Wipf and Stock).

No comments:

Post a Comment