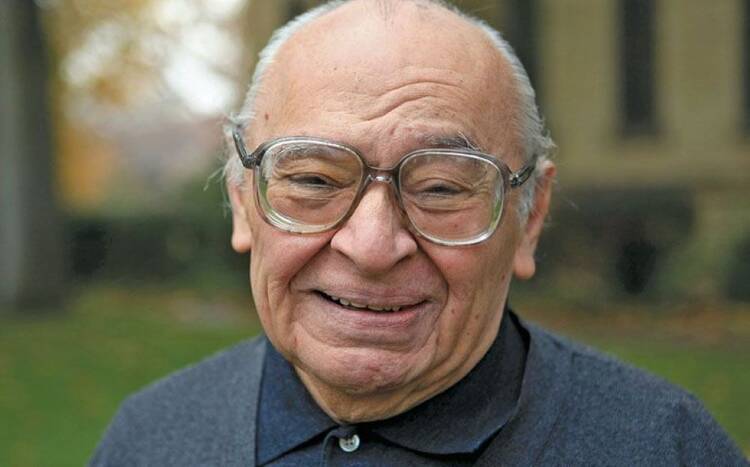

R.I.P. Gustavo Gutiérrez, the prophet who revolutionized Catholic theology for the poor

Though his landmark book, A Theology of Liberation, came from an era of military dictatorships and guerrilla rebels, the real revolution Gustavo Gutiérrez, O.P., helped usher in was upending how authentic Christian faith could be imagined in the world today. Perhaps more than any other theological figure of the past century, this humble Peruvian priest who died Oct. 22 at the age of 96 wrestled with the question that he identified at the heart of liberation theology: “How do you say to the poor, ‘God loves you’?”

In a world that was coming to understand the structural underpinnings of poverty and violence, and in a church only beginning to confront the challenges of modernity, Father Gutiérrez was a prophet who saw clearly how the Christian proclamation of salvation involved not merely the afterlife but included human liberation in this life as well.

The path to that revolutionary text begins in another era of Catholic theology. Father Gutiérrez, as was typical for many talented Latin American seminarians at the time, went to Europe in 1955 to complete his formation. There he encountered a neo-scholastic theology that emphasized the sharp distinction between natural and supernatural realms.

It was a mindset that worked from abstract principles that could be applied anywhere, anytime—context did not matter. The church was understood as the exclusive vehicle for salvation, a societas perfecta that seemed to have little business with the world except functioning like Noah’s ark to usher souls from the earth’s chaos into the heavenly realm. As a priest, Father Gutiérrez would be expected to minister to his people by turning their eyes from this world’s travails to hope in the eternal rest to come. But he could never accept that separation of the Gospel message from real human experience.

Bedridden between the ages of 12 and 18 with a form of polio, Father Gutiérrez was always sensitive to human suffering and indeed had originally intended to study medicine and psychology. Fortunately, his studies in Belgium, France and Rome (where he was ordained a priest in 1959) also included contact with figures of the “new theology,” like Marie-Dominique Chenu and Yves Congar, whose historical studies of ancient and medieval Christian theology forged a path away from abstract neo-scholasticism.

The lesson that Father Gutiérrez would take from these encounters was twofold: First, all theology is contextual and dynamic, and second, behind every theology lies a spirituality. These insights contributed to the dramatic changes associated with the Second Vatican Council.

Yet, for all of its accomplishments, particularly in addressing the “nonbeliever” in the modern world, Vatican II did not sufficiently account for the ones that Father Gutiérrez called the “non-persons.” If the church were going to participate meaningfully in the world, it needed to respond to the reality lived by the majority of earth’s inhabitants—one of poverty and exclusion.

Though he often worked with college students, Father Gutiérrez did not hold a university position until much later in his life. His theology emerged not from the halls of academia but as a response to the questions and concerns he heard from parishioners in the poor Rimac neighborhood of Lima.

Of course, while his theology may have been nourished at this local level, it would quickly make a global impact. In 1968, Father Gutiérrez served on the theological commissions for the seminal Latin American bishops’ conference meeting in Medellín, Colombia. Its documents served as a clarion call for the re-conceiving of the Catholic Church’s role in Latin America and, indeed, the world.

The 1971 publication of A Theology of Liberation (the English translation appeared in 1973) ushered in the dynamic—and controversial—eponymous theological movement and established Father Gutiérrez as its most important voice. Its insights are too numerous to catalog, but it is safe to say that it remains one of the most significant works of 20th-century thought. In it, Father Gutiérrez lays out ideas that he would pursue and refine for the rest of his career.

He describes theology as a “critical reflection on Christian praxis in light of God’s word.” It is a second moment that follows a first moment of mystical encounter with God in and through action in the world. That second moment is crucial because the encounter with poverty and oppression demands not just a one-way Christian response. It calls for a rethinking of Christian ideas themselves in light of those horrible realities, and this dynamic explains the very meaning of the term “liberation theology.”

Father Gutiérrez concluded that in the encounter with violence and poverty, a notion of salvation as an exclusively otherworldly hope was inadequate. Surely the God of the Exodus, the God of the prophets, the God whose reign Jesus preached and the God who took flesh in the world offered more. Father Gutiérrez plumbed the depths of salvation as human beings’ communion with God and with each other. Though its fullness is a future hope, it must begin in the present.

Liberation and salvation, then, are synonymous for the gracious activity of God. Liberation theology is really a theology of salvation, with profound implications for how Christians live, believe, pray and act today. To reflect on Jesus as a liberator, to consider sin in its social and structural dimensions, to ponder the implications of the church’s mission to proclaim truly good news to the poor—these are the fruits of a liberation theology.

Certainly, the new insights generated by liberation theology unsettled traditionalist understandings of the faith and the church. After all, in Latin America, the Catholic Church, with few exceptions, had been a keeper of the status quo since colonial times. It was jarring to many to envision it cutting its alliances with the powerful and proclaiming a salvation that meant integral human development for all peoples. Under liberation theology, peace is not simply the absence of violence but is also the positive presence of justice; it is a personal and structural reality that calls for continual conversion by the church and all of its members.

The signal achievement in Father Gutiérrez’s thinking is his theological treatment of poverty. As a young priest, he wondered how Christianity could speak of it in often beautiful terms, even in the face of poverty’s dehumanizing effects. Clearly, different meanings of the term poverty needed to be distinguished without ignoring its basic, material meaning. But whether it be the lack of material resources to survive or the deprivation of basic human rights, Father Gutiérrez said, poverty in its basic, material meaning is unequivocally evil and must be regarded theologically as sin. This kind of poverty, he would often say, means death, death before one’s time. Any other understanding of poverty comes after this basic one and must address it.

But looking at the Bible and Christian tradition, Father Gutiérrez also identified two “positive” senses to the term poverty. The first is a sense of poverty as humanity’s utter dependence on God. This “spiritual poverty” is one that all people should cultivate, though not by ignoring the reality of material poverty. Rather, Father Gutiérrez linked spiritual poverty to a third sense of poverty as commitment, as solidarity with those who suffer the effects of material poverty.

This solidarity takes on a range of forms, from the merciful care of those who are poor to the prophetic denunciation of the causes of material poverty. Most importantly, the interaction of these three senses of poverty calls for a spirituality, a contemplative-active commitment on the part of the church to make the world more closely resemble the reign of God that Jesus preached.

This spirituality is captured in the often misunderstood phrase “the preferential option for the poor.” By it, Father Gutiérrez gave voice to a disposition, a priority, a way of life that follows the paradoxical Gospel injunction that the “last shall be first.” Christian disciples are called to confront the reality of poverty in all of its complexity. They must prioritize the poor and opt (noting that it is not optional) on behalf of those who are poor.

This principle, which has been adopted and elaborated in modern magisterial texts, has come to be a defining feature of Catholic social teaching. It is more than an ethical injunction, however. In Father Gutiérrez’s work, the preferential option for the poor is a mystical experience; it is God’s own self-revelation. God’s love, expressed time and again in Scripture, is not exclusive but prioritizes those who are weakest. In the words of the 16th-century Dominican friar Bartolomé de Las Casas, about whom Father Gutiérrez produced a massive tome, “God has a very fresh and living memory of the smallest and most forgotten.”

For decades, Father Gutiérrez’s theology drew suspicion in Vatican circles and from those privileged sectors of the Latin American church that felt threatened by its challenges. In the face of queries, suspicions and threats, Father Gutiérrez remained serene and responded to critics thoughtfully. His book The Truth Shall Make You Free offers an account of theology’s relationship to the social sciences and a forceful response to those who would caricature him as a Marxist.

In the end, he was vindicated. Father Gutiérrez was never censured, nor his work ever judged to be heterodox. To his critics’ dismay, he co-published books with the former prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Cardinal Gerhard Müller. By the turn of the new millennium, he had entered the Order of Preachers (Dominicans), taught at their prestigious school in Rome (the Angelicum) and was even given the title magister sacrae theologiae, an honorific bestowed upon the great medieval figures St. Albert the Great and St. Thomas Aquinas.

I recall attending the seminar of a sociologist who claimed to have worked with Father Gutiérrez for a short time in Peru. The speaker lamented that Father Gutiérrez had sadly “left behind the early liberation stuff” when he began writing on spirituality. Nothing could be further from the truth.

From works like We Drink From Our Own Wells or his personal favorite, On Job, Father Gutiérrez demonstrated how profound faith and social commitment are organically intertwined. It is a thoroughly incarnational theology that testifies to God’s presence among human beings and the call of all believers to participate in making the world more closely resemble God’s will for human flourishing.

In that sense, when the poor take center stage, they are not merely receivers of the good news (though they are). Rather, their struggles illuminate the reality of the world and reveal the mysterious presence of God that human language and understanding can only reach toward. This is why Father Gutiérrez repeatedly emphasized that the preferential option for the poor is a theocentric option that believers in the church, much like Job, need to witness; they need to hear God’s own option in revelation and adopt that example in their very lives.

Yes, even the poor need to make the option for the poor.

Most readers overlook the double dedication of A Theology of Liberation. Father Gutiérrez devoted the book to the mestizo Peruvian novelist José María Arguedas, who vividly portrayed the circumstances of Indigenous Andean peoples, and to the Black Brazilian priest Henrique Pereira Neto, who was kidnapped and tortured under military dictatorship. This pair was chosen to symbolize the two great marginalized populations of the continent, Indigenous and African.

Hearing those voices on the margins and putting their concerns at the center of theological thought—that is the lasting legacy of Gustavo Gutiérrez. He did not attempt to make Christianity “relevant,” but he showed that when Christian faith responds authentically to human suffering, it fulfills its deepest calling. Gustavo Gutiérrez was both a prophet who denounced the abuse of the marginalized and a mystic who saw God’s presence where it seems most absent.

No comments:

Post a Comment