Vulnerability isn’t weakness. It’s what makes us human—and able to love.

Editor’s note: This is the third in a series of columns by James Keenan, S.J., on contemporary issues in moral theology.

For many years, I thought of vulnerability as about being wounded, weak, at sea—as primarily a condition that we identify in others whose situation and well-being is compromised in some way. Over time, however, in part through reading philosophers like Emmanuel Levinas, Judith Butler and Jessica Benjamin, I began to see vulnerability as less about being wounded and precarious and more about the human condition that calls us to respond to others.

I began to recognize that the word “vulnerable” does not mean “having been wounded,” but rather “being able to be wounded.” It means being exposed, open or responsive to the other; in this sense, vulnerability is the human condition that allows me to hear, encounter, receive or recognize the other, even if it could lead to me being wounded or injured.

I call the Catholic theological ethics that I write a “vulnerability ethics.” I do not mean vulnerability the way it is used today to refer to some persons whose lives are precarious, as when we refer to vulnerable people. I mean vulnerability as the capacity the human being has to be open and responsive to another human being. This is what many philosophers and a growing group of theological ethicists mean by vulnerability.

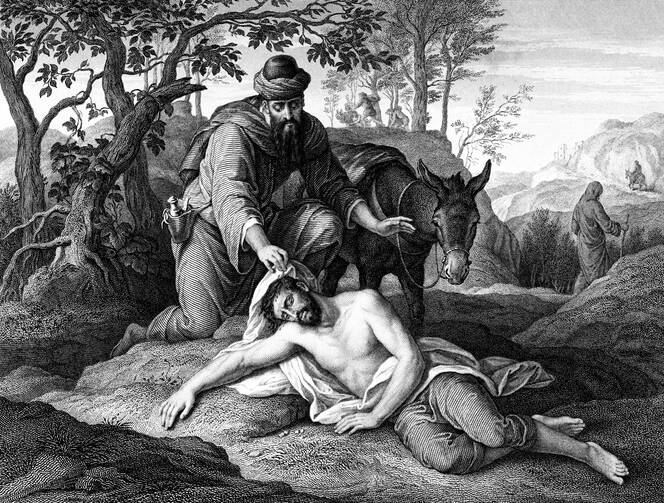

I call this ethics “vulnerability” because it prompts us to the foundational first step of the moral life: the responsive step of recognition that I wrote about for America last month in this space. This is the step that the good Samaritan took toward the wounded man, that the sheep took when they fed the hungry and clothed the naked in Matthew 25, or that the father took as he ran toward his prodigal son—and then as he explained his actions to his resentful son. That first step is the beginning of the response to the Gospel’s call for mercy; it marks the beginning of any moral action. This first step, recognition, is prior to all others. It is only possible to the extent that the human person is vulnerable.

Thus, at Golgotha, I recognize not only the vulnerability of the Savior but the vulnerability of Mary, John and Mary Magdalene in their openness to accompany and witness to Jesus in his pain, sorrow and death. Their vulnerability is a capacious accompaniment, a faithful courageous presence and an unquestionable witness to the ultimate rejection of the Savior.

The mark of our vulnerability is the mark of our humanity. Vulnerability is what, precisely, prompts us to recognize the neighbor in need. It is what fundamentally connects us one to another and it is prior to all other claims on us. It is the very foundation of the ethical life.

Indeed, as the late Irish ethicist, the Rev. Enda McDonagh, taught us: Made in the image of God, we are vulnerable as God is vulnerable. The birth in Bethlehem is as vulnerable as the Incarnation could be. As the Savior dies on the cross, we see in that death his vulnerability to all of us. We are made in his image, he who is the most vulnerable one.

Philosophers, too, realize that vulnerability is the ground of the moral life. Judith Butler insists on vulnerability as foundational: “Ethical obligation not only depends upon our vulnerability to the claims of others but establishes us as creatures who are fundamentally defined by that ethical relation.” Vulnerability defines and establishes us as capable of being moral with one another. As such, our vulnerability precedes everything else that we can say about ourselves as moral human beings.

Emphasizing the priority of vulnerability, Butler writes that it “is prior to any individual sense of self. It is not as discrete individuals that we honor this ethical relation. I am already bound to you, and this is what it means to be the self I am, receptive to you in ways that I cannot fully predict or control.” Butler uses the example of how when any of us are in need of some human assistance, we cry out for help because we know that others, even strangers, can recognize our cry as a moral summons. Vulnerability is prior even to that anonymous moan.

Our vulnerability is, then, what makes us answerable to each other. Indeed, in the Good Samaritan parable, the others do not understand that they were answerable to the injured man. Only the Samaritan is aware of his own vulnerability and it is that which moves him to recognize the wounded man and to respond mercifully.

Vulnerability essentially qualifies us as being bound to and for one another.

Butler’s notion that “I am already bound to you” highlights the priority of vulnerability:

You call upon me, and I answer. But if I answer, it was only because I was already answerable; that is, this susceptibility and vulnerability constitutes me at the most fundamental level and is there, we might say, prior to any deliberate decision to answer the call. In other words, one has to be already capable of receiving the call before actually answering it. In this sense, ethical responsibility presupposes ethical responsiveness.

We have in our skin, our bones, our bodies and our souls the innate, ontological disposition that makes us members of the human community: our vulnerability. That vulnerability is our answerability; it incites and prompts us to recognize, to respond, and to communicate—in short, to love.

I first came upon the connection between vulnerability and recognition not from a philosopher or a theologian, but from the psychoanalyst and feminist theorist Jessica Benjamin, who reflected on infancy and mutual recognition among infants. Mutual recognition is the central experience of infants encountering others like them. After being the object of the attention of people much bigger than themselves, mutual recognition is when an infant finally meets another infant that seems much like itself and yet, not. In such encounters, infants want to touch the face of the other infant; they are fascinated that the child in front of them is just like them. They mutually recognize each other: In that moment, they recognize their humanity and they immediately resonate with one another. They cry when the other cries, smile when the other smiles, touch when the other touches. The experience of mutual recognition plays out again and again as we grow; it occurs with regular frequency throughout our lives, even until the moment we die.

Writing about the moment when an infant encounters another, Benjamin remarks: “Mutual recognition is the most vulnerable point in the process of differentiation.” She adds, “In mutual recognition, the subject accepts the premise that others are separate but nonetheless share like feelings and intentions.”

In a more recent work, she turns again to mutual recognition and finds the language of vulnerability key for recovering and restoring the experience of mutual recognition.

As we mature, the experience of mutual recognition can and should happen time and again as part of our growth as moral agents. The mutual recognition in infancy becomes the foundation for subsequent expressions of due recognition whenever we encounter humanity in its greatest state of precarity or neglect. From that first recognition, where we acknowledge the other’s and our own humanity, we learn to develop an empathetic sense that the other in need is another human being.

Thus, the work of education is to help one another to be vulnerable and vigilant enough so that due recognition and appropriate response to the other is actualized as the worthy alternative to the customary stance of overlooking or neglect, the subject of the next column.

It is worth noting that many feminists insist on the word “vulnerability” to describe the basic source of our responsiveness. If vulnerability meant only or primarily precarity, then we would only want someone not vulnerable, the invulnerable to respond to those in need. But that’s not how it works. Vulnerability is capacious. Indeed, it is most important when we meet one who is in a state of precarity.

The invulnerable are like the biblical figures of Dives, the priest and Levite or the goats. They remain detached, aloof, unresponsive to those in need. No one expects the invulnerable to respond to those in precarity and, certainly, no one wants them to respond with their inevitable condescension.. It is precisely humans in their fundamental humane vulnerability who best respond to those who are precarious. Human vulnerability is the best first responder.

Like the sheep or the watchful father, the good Samaritan is the appropriately vulnerable neighbor who is able to show mercy. Indeed, for centuries, we have used the very name “good Samaritan” to describe the model responder. Like the original good Samaritan, we recognize that we have within us the nature of neighborliness that calls us, in our humanity, to go and do likewise.

Feminists, of course, are mindful of the limits of vulnerability where some (often women) find themselves overwhelmed with so many cares that they become undone by an overabundance of demands on their vulnerability. In a future column, I would like to talk about those who are unfairly burdened by these vulnerabilities in responding to the other. Writers like Lisa Tessman raise the issue in terms of burdened virtues. But here, I want us to recognize vulnerability as the fundamentally human capacity to recognize and respond to another.

More columns from James F. Keenan, S.J.:

“What the disciples learned while grieving in ‘The Upper Room’”

“The great religious failure: not recognizing a person in need”

James F. Keenan, S.J., a moral theologian, is the Canisius Professor at Boston College.

No comments:

Post a Comment