Why Thomas Merton was suspicious of psychedelic drugs

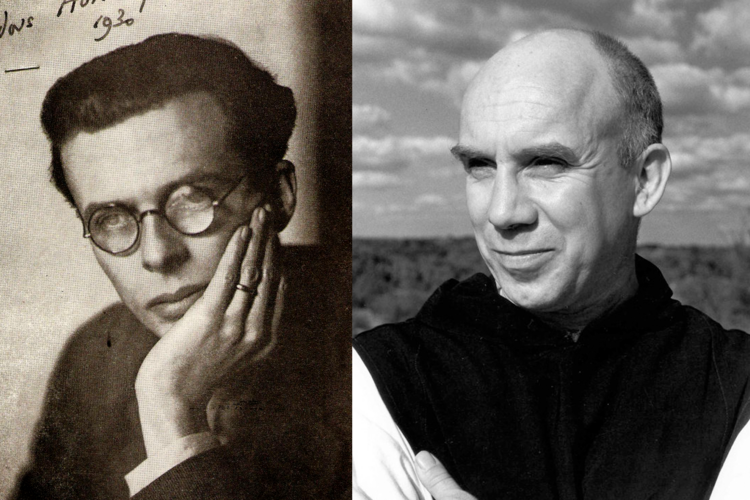

In my early 20s, feeling spiritually unmoored after my undergraduate studies in philosophy, I found myself drawn to certain thinkers who brought intellectual rigor to questions of transcendence. Among these, Thomas Merton and Aldous Huxley loomed large; they introduced me to the study of comparative mysticism and psychedelia, respectively.

Huxley’s long essays “The Doors of Perception” and “Heaven and Hell,” published together in 1954, provide a vivid account of how the psychedelic drug mescaline (an alkaloid derived from the peyote cactus) influenced the author’s spiritual and aesthetic development. Though Merton is rightfully known as a Catholic writer, it was his open-minded writing on Zen and Taoism that nudged me from my youthful atheism to explore meditation and the vast adventure of the interreligious perspective.

Huxley’s work also coaxed me into experimenting with psychedelics myself. I tried psilocybin (the active ingredient in magic mushrooms) while traveling through Holland, where at that time it was legal. It could have gone many different ways, but my experience happened to be comparable to Huxley’s: Psilocybin gave me a skeleton key that allowed me to pry open what had seemed locked doors in several of the world’s sacred texts. I was not what I thought I was—a solid creature with two feet on the ground—but rather a shaky cluster of opinions and reflexes, something spasmodic and vain that the universe was doing. My ego was a tight, defensive shell that tricked itself into believing it was a separate (and maybe more important) vessel than the vast ocean of Being it was navigating with unreliable conceptual maps. I knew my reductive atheistic model of the world could never recover from the revelation.

Now that a “psychedelic renaissance” seems within reach, I find myself concerned about an array of pitfalls.

This was almost a quarter of a century ago. At the time, I would have enthusiastically endorsed the contention that psychedelics should be made more widely available, so more people could partake of the kinds of insights I had gleaned. Now that this scenario is becoming likely, at least in therapeutic settings, and a “psychedelic renaissance” seems within reach, I find myself concerned about an array of pitfalls. One of the most interesting was flagged by Merton in correspondence with Huxley, to whom—it turns out—he owed a certain spiritual debt himself.

Huxley and Merton

Aldous’s grandfather, the biologist and anthropologist T. H. Huxley, coined the word “agnostic” and was known as “Darwin’s bulldog” for his efforts to defend the theory of evolution from Victorian religious attacks. It is an irony of history that his grandson Aldous’s book Ends and Means (1937) awakened a youthful Merton to the notion of spiritual asceticism. Merton writes in his autobiography The Seven Storey Mountain (1948):

Asceticism! The very thought of such a thing was a complete revelation in my mind. The word had so far stood for [an] ugly perversion of nature, the masochism of men who had gone crazy in a warped and unjust society… [But Huxley] showed that this negation… was a freeing, a vindication of our real selves, a liberation of the spirit from limits and bonds that were intolerable, suicidal…. [Pages 185-186]

Merton read Huxley’s book several times and was moved to write a review of it. Such was Merton’s respect for him that decades later, when psychedelia began to shimmer in the zeitgeist, endorsed in no small part by Huxley’s own essays and journalism, the monk wrote to the novelist about the spiritual promises and dangers of psychoactive substances.

Merton was quick to admit he had never taken psychedelic drugs, and it seems he never did. But he had searching questions and challenges for Huxley, which I’ve distilled to the questions below:

1. Are we not endangering the whole conception of mystical experience in saying that it is something that can be produced by a drug?

2. Ought we not to distinguish an experience which is essentially aesthetic and natural from an experience which is mystical and supernatural?

3. The moment such an experience is conceived as dependent on and inevitably following from the casual use of a material instrument, does it lose the quality of spontaneity, freedom and transcendence that make it truly mystical?

Elaborating on point two above, Merton ponders: “It seems to me that a fully mystical experience [is] a direct spiritual contact of two liberties…” One liberty is the personality of the spiritual aspirant, and the second is God, “not as an ‘object’ or as…‘Him in everything’ nor as ‘the All’ but as…I AM.” For Merton, the presence of God-as-Person “depends on the liberty of that Person. And lacking the element of a free gift…the experience would lose its specifically mystical quality.” Psychedelic substances, in other words, functioned like buttons pressed for revelation-on-demand; Merton worried that habitual dependence on an instant-mysticism drug could ruin a truly mystical vocation, “if not worse.”

Huxley replied cordially, admitting that Merton’s challenges were “interesting and difficult.” Huxley mentioned the nascent psychedelic research into curing alcoholism, using LSD “within a religious, specifically Catholic, frame of reference, and achieving remarkable results, largely by getting patients to recognize that the universe is profoundly different from what…it had seemed to be.” He noted forthrightly that while about 70 percent of the test subjects’ experience was “paradisal,” the rest found it “infernal,” and he drew a connection between this unpredictability and the experience of traditional church mystics: A “great many of the experiences of the desert fathers were negative.” Speaking of his own psychedelic voyages, Huxley quotes William Blake’s phrase “Gratitude is heaven itself” and declares: “and I know now exactly what he was talking about…. One understands such phrases as ‘Yea, though He slay me, yet will I trust in Him.’… Finally, an understanding, not intellectual…of the affirmation that God is love.”

Merton objected to “an easily available spiritual experience.”

Huxley’s response involves practical ethics (here is the good these drugs have done for many addicts; here is the good they have done for me) and allows for mystery. If Merton’s concern is that psychedelics are like pressing a button, Huxley assures him that the button’s wiring is still unknown. But he did not engage with the theological implications of Merton’s argument, which are more slippery. Clearly, he didn’t assuage Merton’s concerns about “illuminism,” which seems to be a species of idolatry. In his last book, The Inner Experience, published in 2003 long after his death in 1968, Merton wrote:

…the one great danger that confronts every man who takes spiritual experience seriously is the danger of illuminism or, in Mgr. Knox’s term, “enthusiasm.” Here the problem is that of taking one’s subjective experience so seriously that it becomes more important than truth…than God. [Page 106]

Referring to drug experiments (including Huxley’s self-experimentation with LSD and mescaline) to induce spiritual visions and mystic intuition, Merton cautions that we run the risk of “organized and large-scale illuminism. This would mean that an easily available spiritual experience would be sought for its own sake. But this kind of attachment is…more dangerous than any other” (Page 107). He quotes St. John of the Cross warning about consenting too easily to visions, even when they seem to emanate from divine sources:

Although all these things may happen to the bodily senses in the way of God we must never rely on them or admit them, but…always fly from them, without trying to ascertain whether they be good or evil; for the more completely exterior and corporeal they are, the less certainly are they of God…he that esteems such things…places himself in great peril of deception; and at best he will have…a complete impediment to the attainment of spirituality. [See Ascent of Mount Carmel, Pages II, XI and 2-3.]

It appears Merton’s worries about illuminism are at least twofold. First, there is the concern that any striking “vision” constituting a clear break from the normal modes of perception is inherently worthy of suspicion as to its heavenly vs. hellish origins. There is also Merton’s objection to “an easily available spiritual experience,” with its implication that spiritual insight must be the result of patient searching (the path finding you, as much as you finding the path) or it is necessarily dangerous.

Whether Merton is right on the second count or not, I endorse the claim that spirituality is fundamentally at odds with consumer culture, wherein you can order something on demand. In our current capitalistic system, the therapeutic has become ascendant because it is the fruit of that culture. It promises specific outcomes, like “wellness” or improved life satisfaction, and the prevailing understanding is that such results should be available to anyone who wants them, provided they put in the time and money.

Anything that helps us approach the sublime nature of consciousness may be intrinsically valuable but not necessarily “therapeutic.”

If Merton is arguing that the spiritual can never be so neatly corralled, then his thinking aligns with my own instinct to protect what I perceived psychedelics to be after I tried them—a sort of metaphysical teaching technology—from people who would hand it out as a mental health panacea. Put another way, anything that helps us approach the sublime nature of consciousness may be intrinsically valuable but not necessarily “therapeutic.” In fact, it might be anything but.

One heartrending account of a “theological reckoning” with the zealous push to fuse psychedelia with mental healing comes from the writer Rachel Petersen. Writing for the Harvard Divinity Bulletin, she describes her first treatment for depression as something beatific:

under a high dose of psilocybin, I had the most religious experience of my life. An encounter with divine darkness, a nothingness that held and beheld me, benevolently welcoming me into my rightful place in the order of things.

But only a week later, her second session turned infernal, opening the gates to a pervasive sense of dread, a horror vacui that stalked her afterward: “The very quality that made my first experience so profound—its felt sense of authority—made my second so indelibly harrowing, a trip after which nothing felt the same.”

Ms. Petersen realized the hard way that, as she put it, the mainstreaming of psychedelia (and previously esoteric practices like mindfulness meditation) is not without risk “when technologies of transcendence are stripped from their spiritual and religious contexts and presented as psychological treatments.” She echoes Merton’s suspicion that a “transactional” relationship with spiritual technologies is faulty from the outset:

Psychedelic science does an odd dance with the spiritual. On the one hand, studies (mostly out of Johns Hopkins University) have popularized the notion that a mystical-type experience leads to better therapeutic outcomes. This frame reduces transcendence to its therapeutic potential—a breathtakingly transactional posture to the divine that creates a sort of tautology whereby the mystical is therapeutic because the therapeutic is mystical. This is most evident in the narrow definition used in the Mystical Experience Questionnaire (MEQ): to qualify for a “complete mystical experience,” one must report a concurrent “positive mood.”

As anyone who has grappled with the Sorrowful Mysteries of the rosary understands, spirituality encompasses universes beyond “a positive mood.” By some lights, therapy and spirituality will appear outright antithetical.

But I also resist Merton’s suggestion that a substance-induced spiritual experience is less “real” than, for example, the visions of William Blake, which were apparently a function of how his mind naturally worked. If we are tempted to see psychonauts as “spiritual dopers” and the likes of Blake as the Michael Phelps of visions—i.e., naturally gifted, and therefore their experiences more permissible—I wonder if it is because our Western religious traditions do not incorporate the use of psychedelic substances in a ritualistic setting. Besides, isn’t it also a spiritual hazard to counter drug idolatry with a counter-egotism that proclaims oneself a “real” mystic because one never uses such aids?

God-generating

Some have suggested that psychedelics can serve a sacramental role, and I admit I’m intrigued by the prospect. I would note here that the term “entheogen” (god-generating) has replaced “psychedelic” (mind-manifesting) in many circles. The latter term was coined by the psychiatrist Humphrey Osmond, a friend of Huxley’s, while “entheogen” originated with the classicist Carl Ruck in the late 1970s. It is impossible not to notice the implied difference between their two meanings, the one quite neutral and the other explicitly theological.

But what matters most is not whether these substances are used, but how and why. Psychological and social context (the “set and setting”) are vital determinants of whether an individual user is opening a door to heaven or hell, to deeper realization or deeper delusion. Whether there can be a sound ethics of the use of these substances in spiritual development is an urgent question that cannot go ignored by religious leaders as trials with these substances move closer to the mainstream.

As we work through it, Merton’s thoughtful critique of entheogen-driven spirituality is one intriguing area of consideration. In a recorded talk he gave on Celtic monasticism, he explains that Irish monks associated pilgrimage with a kind of martyrdom. He describes a practice of seafaring monks boarding a boat, probably a currach, a small wood-framed vessel covered in sewn ox-hides. Shoved from the shore, these monks would take no oars to guide or power their way. All would become passengers, giving over their fate to ocean tides.

This, perhaps, is Merton’s ideal: understanding the spiritual life as a pilgrimage, or a boat with no oars. It is a state of obedience, of ritual suffering, of waiting. Maybe he saw taking a drug to make this voyage as cheating: hopping on a plane and jetting to America in a few hours instead of enduring the supposed route of St. Brendan.

I don’t know if taking entheogens for the purpose of spiritual growth is an unfair shortcut. My intuition tells me that currachs can take many forms. I’m reminded that there is an entire genre of ancient Irish poetry called immrama. These poems are about leaving the safety of home shores, encountering strange islands and bizarre creatures in a hostile ocean. But the goal of these seafarers was not adventure, and certainly not conquest or riches or personal glory. Nor was it therapy. It was nothing more, nor less, than the “white martyrdom” of pilgrimage: piercing mundanity to reveal the oceanic mystery at the heart of Being.

Colm O’Shea (colmoshea.com) teaches essay writing at New York University. He is the author of the science-fiction novel Claiming De Wayke (Crossroad Press) and the academic monograph James Joyce’s Mandala (Routledge).

No comments:

Post a Comment