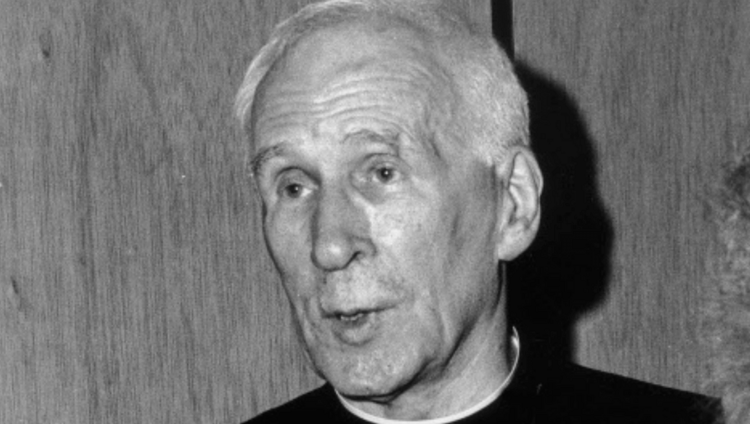

From 1991: Avery Dulles on Henri de Lubac

Editor’s note: This essay originally appeared in the Sept. 28, 1991 issue of America, titled “Henri de Lubac: In Appreciation.”

Together with Rahner, Lonergan, Murray, von Balthasar, Chenu and Congar, Henri de Lubac stood among the giants of the great theological revival that culminated in Vatican II (1962-65). His death on Sept. 4, 1991, leaves Yves Congar, O.P., ill and hospitalized, as the only surviving member of this brilliant Pléiade.

Together with Rahner, Lonergan, Murray, von Balthasar, Chenu and Congar, Henri de Lubac stood among the giants of the great theological revival that culminated in Vatican II.

Born in 1896, de Lubac entered the Society of Jesus in 1913. After serving in the army and being severely wounded in World War I, he studied for the Jesuit priesthood under excellent masters. During his studies he gained an enthusiasm for Thomas Aquinas, interpreted along the lines suggested by Blondel, Rousselot and Maréchal. Without any specialized training or doctoral degree he was assigned to teach theology in the Catholic faculty at Lyons, where he taught, with some interruptions, from 1929 to 1961. There, and in his occasional courses at the neighboring Jesuit theologate at Fourvière (1935-40), de Lubac quickly began to forge new directions in fundamental theology and in comparative religion.

De Lubac’s first book, Catholicism (1938), was intended to bring out the singular unitive power of Catholic Christianity and its capacity to transcend all human divisions. Developing his interest in the fathers of the church, he founded in 1940, with his friend Jean Daniélou, S.J., a remarkable collection of patristic texts and translations, Sources chrétiennes, which by now includes more than 300 volumes. During the Nazi occupation of France, he became coeditor of a series of Cahiers du Témoignage chrétien. In these papers and in his lectures, de Lubac strove particularly to exhibit the incompatibility between Christianity and the anti-Semitism that the Nazis were seeking to disseminate among French Catholics. On several occasions his friends had to spirit him away into hiding to prevent him from being captured and executed by the Gestapo, as happened to his close friend and colleague, Yves de Montcheuil, S.J.

After the war, de Lubac developed his theology in several directions. In an important study of medieval ecclesiology, Corpus mysticum (completed in 1938 but not published until 1944), he demonstrated the inner bonds between the church and the Eucharist. To his mind, the individualism of modern Eucharistic piety was a step backward from the great tradition, which linked the Eucharist with the unity of the body of Christ. Seeking to stem the spread of Marxian atheism, he wrote on the intellectual roots of French and German atheistic socialism. He also composed several shorter works on the knowability of God and the problems of belief.

Seeking to deflect accusations against the Society of Jesus in France, the Jesuit General, John Baptist Janssens, required de Lubac to submit his writings to a special process of censorship.

De Lubac’s most famous work, Surnaturel (1946), maintains that the debate between the Baianists and the scholastics in the 17th century rested on misinterpretations both of Augustine and of Thomas Aquinas. Both parties to the debate, it maintains, were operating with philosophical and juridical categories foreign to ancient theology. Contemporary neoscholastics, especially in Southern France and Rome, taking offense at de Lubac’s attack on their methodology and their doctrine, interceded with the Holy See for a condemnation. When Pius XII published the encyclical Humani generis (1950), many believed that it contained a condemnation of de Lubac’s position, but de Lubac was relieved to find that the only sentence in the encyclical referring to the supernatural reproduced exactly what he himself had said in an article published two years before.

Seeking to deflect accusations against the Society of Jesus in France, which was being accused of promoting a supposedly modernistic “new theology,” the Jesuit General, John Baptist Janssens, removed de Lubac and several colleagues from their teaching positions and required them to submit their writings to a special process of censorship. These regulations did not affect de Lubac’s work on Origen’s interpretation of Scripture, Histoire et Esprit, which came off the press in 1950, just as the storm was breaking. Because of the restrictions placed on his theological research, de Lubac in this period turned toward the study of non-Christian religions. He published three books on Buddhism, which interested him as an example of religion without God.

In 1953, during his “exile” in Paris, de Lubac published a popular work on the church constructed out of talks given at days of recollection before the war. (He was embarrassed by the triumphal sound of the title given to the English translation, The Splendor of the Church, as well as by suspicions in some quarters that his expressions of love and fidelity toward the church in this book were intended to atone for the offense given by his previous works.) Pained though he was by the widespread doubts about his own orthodoxy, de Lubac was even more distressed that some disaffected Catholics used his troubles as an occasion for mounting bitter attacks on the magisterium and the papacy.

The clouds over de Lubac began to dissipate in the late 1950’s. In 1956 he was permitted to return to Lyons, where he began research for his major study of medieval exegesis, which was to appear in four large volumes between 1959 and 1964. In 1960 Jesuit superiors, fearing that the works of Teilhard de Chardin were about to be condemned by Roman authorities, asked de Lubac to write in defense of his old friend, who had died in 1955. Beginning in 1962, de Lubac published a series of theological works on Teilhard and edited several volumes of Teilhard’s correspondence. Probably more than any other individual, de Lubac was responsible for warding off the impending condemnation.

During the council de Lubac established a close working relationship with Cardinal Karol Wojtyla, who as John Paul II was to elevate him to the rank of cardinal in 1983.

In 1960 Pope John XXIII, who, as papal nuncio in France, had gained an admiration for de Lubac, appointed him a consultant for the preparatory phase of Vatican II. As a consultant, he found much to criticize in the schémas prepared by the neoscholastic Roman theologians. These schemas, which contained statements intended to condemn both him and Teilhard de Chardin, were rejected when the council fathers assembled. De Lubac continued to serve as an expert (peritus) at the council, making his influence felt on many documents such as the Constitution on Divine Revelation and the Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World. Some of his ideas are reflected also in the Decree on the Church’s Missionary Activity and in the Declaration on the Non-Christian Religions.

Greatly esteemed by Pope Paul VI, de Lubac was one of the 11 council theologians chosen to concelebrate with him at the Eucharist preceding the solemn promulgation of the Constitution on Revelation in November 1965. (During the council de Lubac established a close working relationship with Cardinal Karol Wojtyla, who as John Paul II was to elevate him to the rank of cardinal in 1983.) For several years after 1965, de Lubac traveled widely to explain the achievements of the council. He visited the United States and Latin America, as well as many parts of Europe. He published an important commentary on the Constitution on Revelation, and in other writings sought to clarify the relationships between primacy and collegiality, and between the universal and the particular church. Perceiving the advent of a new crisis of faith, he wrote La foi chrétienne and L’Eglise dans la crise actuelle (both 1969). His preoccupations with the present state of the church, however, did not prevent him from continuing his studies in the history of theology, such as his work on Pico della Mirándola (1974) and on the spiritual posterity of Joachim of Fiore (2 volumes, 1979, 1981).

By his own admission, de Lubac was not a systematic thinker. He never tried to articulate any set of first principles on which to base his philosophical or theological findings. Many of his books are composed of historical studies loosely linked together. Although he made forays into many areas, he never composed a treatise on any of the standard theological disciplines. In his last work, an autobiographical reflection published in 1989, he chided himself for having failed to undertake the major work on Christology that he had once projected.

De Lubac’s exegesis has often been depicted as anti-critical or precritical, but it was neither. De Lubac practiced what Paul Ricoeur was to call a “second naiveté.”

For all that, de Lubac’s work possesses a remarkable inner coherence. As his friend and disciple Hans Urs von Balthasar pointed out, de Lubac’s first book, Catholicism, is programmatic for his entire career. The various chapters are like limbs that would later grow in different directions from the same trunk. The title of this youthful work expresses the overarching intuition. To be Catholic, for de Lubac, is to exclude nothing; it is to be complete and comprehensive. He sees God’s creative and redemptive plan as including all humanity and indeed the entire cosmos. For this reason the plan demands a unified center and a goal.

That center is the mystery of Christ, which will be complete and plainly visible at the end of time. The universal outreach of the church rests on its inner plenitude as the body of Christ. Catholicity is thus intensive as well as extensive. The church, even though small, was already Catholic at Pentecost. Its task is to achieve, in fact, the universality that it has always had in principle. Embodying unity in diversity, Catholicism seeks to purify and elevate all that is good and human.

In the patristic and early medieval writers de Lubac found an authentic sense of Catholicism. He labored to retrieve for our day the insights of Irenaeus and Origen, Augustine and Anselm, Bernard and Bonaventure. He remained a devoted disciple of Thomas Aquinas, whom he preferred to contemplate in continuity with his predecessors rather than as interpreted by his successors.

In de Lubac’s eyes, a serious failure occurred in early modern times, and indeed to some extent in the late middle ages. This was the breakdown of the Catholic whole into separate parts and supposedly autonomous disciplines. Exegesis became separated from dogmatic theology, dogmatic theology from moral, and moral from mystical. Worse yet, reason was separated from faith, with the disastrous result that faith came to be considered a matter of feeling rather than intelligence.

One step in this process of fragmentation, for de Lubac, was the erection of an order of “pure nature” in the scholasticism of the Counter Reformation. The most controversial act of de Lubac’s career may have been his attack on Cajetan and Suarez for their view that human nature could exist with a purely natural finality. For de Lubac, the paradox of a natural desire for the supernatural was built into the very concept of the human.

De Lubac was convinced that the newness of Christ was both a fulfillment and a gift. Somewhat as nature was a preparation for grace, while grace remained an unmerited gift, so the Old Testament foreshadowed the New, without however necessitating the Incarnation. In his exegesis, de Lubac sought to show how the New Testament gave the key to the right interpretation of the Old Testament, which it fulfilled in a surpassing manner.

Terms such as “liberal” and “conservative” are ill suited to describe theologians such as de Lubac. If such terminology must be used, one would have to say that he embraced both alternatives.

De Lubac’s exegesis has often been depicted as anti-critical or precritical, but it was neither. It might with greater justice be called, in Michael Polanyi’s terminology, postcritical. De Lubac practiced what Paul Ricoeur was to call a “second naiveté.” After having studied the literal sense of Scripture with the tools of modern scholarship, he returned to the symbolic depths of meaning with full awareness that these depths go beyond the literal. The “spiritual” meaning transcends, but does not negate, the “historical.”

The root of de Lubac’s theology stands an epistemology that accepts paradox and mystery. Influenced by Newman and Blondel, Rousselot and Maréchal, he interpreted human knowing as an aspect of the dynamism of the human spirit in its limitless quest for being. Without this antecedent dynamism toward the transcendent, the mind could form no concepts and arguments. Concepts and arguments, however, arise at a second stage of human knowing and are never adequate to the understanding they attempt to articulate. In every affirmation we necessarily use concepts, but our meaning goes beyond them.

De Lubac was satisfied that Vatican II had overcome the narrowness of modern scholasticism, with its rationalistic tendencies. The council, he believed, had opened the way for a recovery of the true and ancient tradition in all its plenitude and variety. But Catholics in France, and indeed in many parts of the world, having imbibed too narrow a concept of tradition, took the demise of neoscholasticism as the collapse of tradition itself. In postconciliar Catholicism de Lubac perceived a self-destructive tendency to separate the spirit of the council from its letter and to “go beyond” the council without having first assimilated its teaching. The turmoil of the postconciliar period seemed to de Lubac to emanate from a spirit of worldly contention quite opposed to the Gospel.

For his part, de Lubac had no desire to innovate. He considered that the fullness was already given in Christ and that the riches of Scripture and tradition had only to be actualized for our own day. In a reflection on his own achievement he wrote: “Without pretending to open up new avenues of thought, I have rather sought, without any archaism, to make known some of the great common sources of Catholic tradition. I wanted to make it loved and to show its ever-abiding fruitfulness. Any such task required a process of reading across the centuries rather than critical application at definite points. It excluded too privileged an attachment to any particular school, system or period” (Mémoire sur l’occasion de mes écrits).

Terms such as “liberal” and “conservative” are ill suited to describe theologians such as de Lubac. If such terminology must be used, one would have to say that he embraced both alternatives. He was liberal because he opposed any narrowing of the Catholic tradition, even at the hands of the disciples of St. Thomas. He sought to rehabilitate marginal thinkers, such as Origen, Pico della Mirándola and Blondel, in whom he found kindred spirits animated by an adventurous Catholicity of the mind. He reached out to the atheist Proudhon and sought to build bridges to Amida Buddhism.

But in all of these ventures he remained staunchly committed to the Catholic tradition in its purity and plenitude. He humbly and gratefully accepted what the tradition had to offer and made it come alive through his eloquent prose and his keen sense of contemporary actualities. His eminent success in enkindling love for Christ and the church in the hearts of his readers stemmed, no doubt, from his own devotion, humility and selfless desire to serve. The suffering of his long years of adversity, including two world wars and decades of great tension in the church, are still bearing fruit. In the last few years, as his earthly life drew to a close, his disciples and admirers became more numerous and influential. De Lubac’s creative reappropriation of the ancient tradition has earned him a place of honor in a generation of theological giants.

No comments:

Post a Comment