07 November 2018 | by Liz Dodd , James Roberts

A dialogue of silence: Remembering Thomas Keating

The Tablet

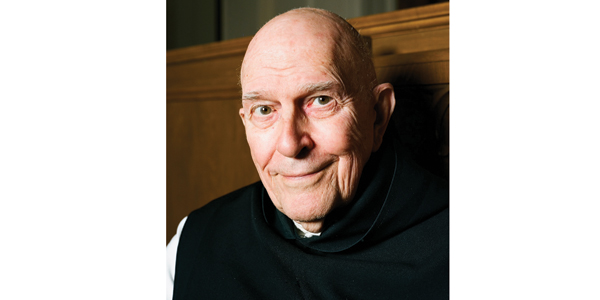

Thomas Keating

Remembering Thomas Keating

LIZ: High in the silver mine mountains above Mexico

City, a 95-year-old monk from New York led me into the presence of God.

He did it over YouTube, on a video that I was streaming into my tent

using internet borrowed from a cantina over the road. I discovered

Thomas Keating late in my journey cycling around the world and – it

turned out last week – late into the Trappist abbot’s own journey. I’d

had Invitation to Love: The Way of Christian Contemplation on my Kindle

for a few weeks before I opened it one day. The first words I read

turned everything I’d thought I’d known about contemplative life on its

head: “The spiritual journey is a training in consent to God’s presence

and to all reality.”Living surrendered to the uncertainty of life on the road for 18 months – vulnerable, often alone and dependent – had cultivated in me just that kind of consent to reality: I just hadn’t realised it came hand-in-hand with a consent to God’s presence. What Keating seemed to be saying – that God is within reality so expansively that being surrendered to the present moment is to be present to him – made perfect sense; what was more, I couldn’t believe a Catholic was saying it. The more I read, the more I was hooked.

JAMES: Unlike most Trappists, who adhere to a vow of silence, Thomas Keating was given licence to go out into the world and explain how God himself is, in fact, silence. In a three-day retreat led by Keating in Leeds nine years ago, I joined 25 others to learn how to find God, and the silence that is God.

Of course, this phrasing is loaded. The word “find” implies activity, whereas the techniques of the “Centring Prayer” that Keating and his fellow Trappist writer Basil Pennington offer are about not doing, rather than doing; about not trying to do anything, rather than trying not to do anything. Thoughts are an impediment. But while we cannot try to stop thinking, we can allow our thoughts to pass, so that we enter, or are entered by, a different sort of consciousness.

I arrived carrying my false self – the bundle of mistaken hopes and desires, illusory beliefs, and misleading emotions we all lug around with us – and Keating pointed the way towards laying down the burden. He was 86. He knew the journey and was talking from experience.

I remember best his stature, his habit, the cadences of his voice, the way he sat. We learn unconsciously from the body language of those around us, and his demeanour when resting and praying rubbed off. His own calm self-discipline brought the necessary order to the sessions – he would give two hour-long talks each day between the prayer times. His only demand was for silence, about which he was uncompromising.

LIZ: Keating’s instructions – drawn, he reminds us, from the Gospel (Matthew 6:6) and from ancient Christian traditions – are simple: sit in silence for about 20 minutes, with the intention of loving God. If thoughts – even holy ones – arise, let them go. It can help to have a “sacred word” to use when your mind wanders, a phrase that recalls you to God, that you repeat mentally until you feel at rest again.

When I started practising centring prayer I was immediately struck by how closely it resembled “mindfulness meditation”, which involves sitting and observing your thoughts passing, with the intention of remaining in the present moment. One day, the jigsaw took shape, and I realised that the two processes felt so similar because they were: but what mindfulness calls the “present moment”, the tradition of Christian prayer, from which Keating draws, calls God. It was a quietly earth-shattering revelation, particularly when I recalled the times on my journey when I’d felt like God had abandoned me: God was always there, fully present, in each moment; it was the sense of separation from him that had been illusory.

JAMES: For the Trappist, the “room” of Matthew 6:6 is his cell. So it looks like the monk is intent – perhaps a little selfishly – on escaping from the temptations and wickedness of the world. But is this really what is going on? In Invitation to Love, Keating writes: “Saint Anthony of Egypt headed for the desert. In the fourth century, the desert was believed to be the stronghold of the Devil, his military-industrial complex, so to speak, where he devised projects to destroy lives, communities, and nations, worldwide. Thus, Anthony marched into the Devil’s concentration of power. It is a mistake to think of monastic life as an escape from the world.”

And what is the monk’s reward? In Keating’s terms, it is the shedding of the false self – the dismantling of the thick, high barrier to God that we have allowed to be built inside us.

LIZ: In an interview he gave when his book The Power of Silence was launched in 2016, Cardinal Robert Sarah – hero to many conservative Catholics – gave a surprising endorsement of the writings of Keating – hero to many progressive Catholics. Sarah approvingly quotes Keating’s gloss on St John of the Cross’ famous aphorism: “God’s first language is silence.” The Trappist made this one of his own favourite sayings, and added: “Everything else is a poor translation. In order to understand this language we must learn to be silent and rest in God.”

The books of Fr Keating and Fr Pennington have aroused controversy. Although they insisted that the then-Cardinal Ratzinger’s 1989 broadside, “On Some Aspects of Christian Meditation”, was not directed at centring prayer, some people interpreted its warning against trusting in spiritual “techniques” whose origins lie in Eastern spirituality as a covert warning.

Keating’s location of God in silence might be one of very few places where Cardinal Sarah and I find common ground. The present moment – and thus God – holds within itself both good and evil, left and right, liberal and conservative, the Traditional Latin Mass and the Novus Ordo. Keating suggests that these categories, and the activities that flow out of them – conflict, war, racism, oppression – are indicative of a cultural psyche that has not fully matured. “The primary issue for the human family at its present level of evolutionary development”, he writes, “is to become fully human. But that, as we have seen, means rediscovering our connectedness to God.” It is a message that could be as at home in a homily at the Brompton Oratory as in a speech at a CND demonstration.

JAMES: Keating argued that the false self – in each and every individual – is the root cause of these conflicts and confrontations. He describes how a twice-daily practice of centring prayer, letting go of thoughts, emotions and images, will gradually enable us so to experience deep silence and cultivate our receptivity to God’s active presence in our life, and allow God to heal the false self in us.

No one has questioned the silence of God in the face of unimaginable suffering more incisively and eloquently than Dostoevsky in The Brothers Karamazov. Ivan describes the torments of a young girl at the hands of her respectable parents to his devout younger brother Alyosha. “Can you understand why a little creature, who can’t even understand what’s done to her, should beat her little aching heart with her tiny fist in the dark and the cold, and weep her meek unresentful tears to dear, kind God to protect her?” For Ivan, Heaven cannot be built on the suffering of even one innocent child.

Keating’s answer is the Christian answer, or the best that Christians can come up with: “Jesus allowed himself to experience the utmost suffering and rejection as part of being sent, thus manifesting the inner nature of Ultimate Reality as infinite compassion and forgiveness.”

No comments:

Post a Comment