25 July 2018 | by Tom Burns

Crisis in the Church: Humanae Vitae 'the greatest shock since the Reformation'

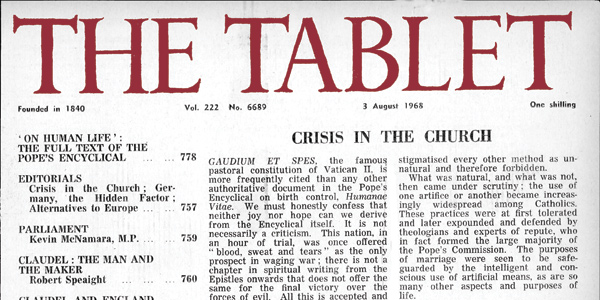

How The Tablet reported on Humanae Vitae in August 1968

Humanae Vitae at 50

In his editorial in the 3 August 1968 issue

of The Tablet, Tom Burns insisted that “We who are of the household of

the faith and can think of no other have the right to question, complain

and protest, when conscience impels.” An explosive row followed. Fifty

years later, many consider Humanae Vitae to be past history; as far as

the magisterium is concerned, it is not. Here is the text of that

editorial in full: the exclusive language jars, but the power of Burns’

words can still be felt. His verdict remains prescient. The matter is

still before the bar of conscience.

More on Humanae Vitae at 50

Fr Jock Dalrymple: although dismayed by the ban on contraception, he decided to stay in the Church

Michael Winter: being ordered to promulgate the encyclical cost this committed priest his vocation

From the Editor's desk: The return of joy and hope

Gaudium et Spes, the famous pastoral constitution of Vatican II, is more frequently cited than any other authoritative document in the Pope’s Encyclical on birth control, Humanae Vitae. We must honestly confess that neither joy nor hope can we derive from the Encyclical itself. It is not necessarily a criticism. This nation, in an hour of trial, was once offered “blood, sweat and tears” as the only prospect in waging war; there is not a chapter in spiritual writing from the Epistles onwards that does not offer the same for the final victory over the forces of evil. All this is accepted and endured by convinced Christians the world over. In their trials, indeed, they could find their exemplar in Pope Paul himself: his mortified, self-spending life is totally dedicated to the service of God and mankind. Every call, then, in his Encyclical for a deepening of dedication in married life will be understood and welcomed.

The Experience of Marriage

To many married people, however, there is a betrayal of their dedication precisely in indiscriminate child bearing on the one hand or the alternative of calendar-spaced love-making or total abstinence on the other. These alternatives are more repugnant to a human couple in love than artificial devices; they are less natural in the sense of being less consonant with their continuing close relationship.

Christian couples today are, if anything, ahead of their forebears in realising the unique sacramental nature of marriage, the devotion and discipline that goes with it, the joy and fulfilment it brings through parenthood. None of this teaching, which forms part of the Encyclical, will be lost on them and it bears repetition to a world where these values and standards are discounted.

Responsible parenthood is the keynote of Christian marriage. It has been interpreted over the last few years to include the limiting of families to a size in keeping with the health, means and general circumstances of the parents. That there should be limitation of this kind nobody denies and in fact this Encyclical endorses the idea. How the limitation should be effected is the question.

Before the Encyclical, it had come to be widely accepted among Catholics that the obvious rational way to reconcile the needs of married love and responsible procreation was by way of contraception. Papal authority only went so far as to say that so-called “natural” contraception – i.e. the use of the safe period – was legitimate, and stigmatised every other method as unnatural and therefore forbidden.

What was natural, and what was not, then came under scrutiny; the use of one artifice or another became increasingly widespread among Catholics. These practices were at first tolerated and later expounded and defended by theologians and experts of repute, who in fact formed the large majority of the Pope’s Commission. The purposes of marriage were seen to be safeguarded by the intelligent and conscious use of artificial means, as are so many other aspects and purposes of life.

The Failings of Natural Law

“Such questions,” says the Encyclical, “required from the teaching authority of the Church a newer and deeper reflection upon the principles of the moral teaching on marriage: a teaching founded on the natural law, illuminated and enriched by divine Revelation.”

Two questions must inevitably be asked: where is the new and deeper reflection? What evidence is adduced to support by divine Revelation the teaching of the natural law? It is a matter of observation that the whole notion of the natural law is now widely rejected. It is rejected more often than not because its upholders all too often seem to suggest that they believe in a certain fixed, unchanging pattern of conduct as imposed on man from above, a pattern which he must accept whether he likes it or not, whether he sees the point of it or not. But in fact the natural law is not imposed in this way. It is discovered by man’s use of his own reason, since it is the law of his own fulfilment. As Gaudium et Spes itself puts it: “A true contradiction cannot exist between the divine law pertaining to the transmission of life and those pertaining to the fostering of authentic conjugal love.” It is indeed difficult not to sympathise with those who have found, by sad experience, that “authentic conjugal love” has not in fact been fostered by attempts to observe the “divine law” as expounded by the Church. They have come to the conclusion that the divine law is discovered through their honest attempts to live a fully human, mutually responsive, dedicated conjugal life.

It must be seen as difficult for the candid mind to accept the apparent casuistry which justifies the use of rhythm whilst rejecting the use of chemical or mechanical means even though, as the Encyclical says, “in both cases the married couples are at one in the positive intention of avoiding children … seeking the certainty that offspring will not arise”. People can hardly be blamed for seeing as sophistical this permission for the use of the infertile period side by side with the assertion that “each and every marriage act must remain open to the transmission of life”. This last view, taken in its rigour in the past, has resulted in the limitation of intercourse to occasions when conception was genuinely possible. The move away from this extreme rigorism to the toleration (indeed at times the positive encouragement) of the use of the infertile period has been part of that ongoing development in the Church’s teaching which during the last few years has been clearly passing to a new stage.

The very setting-up of the Commission on the subject, the findings of a majority of its members, the known sympathy expressed both by bishops and priests, the difficulties and witness of married people bound by the former discipline – all these seemed to be paving the way for a new and deeper reflection on the principle of the Church’s moral teaching on marriage. It was beginning to enable Catholics to play their part in demographic studies and social efforts of all kinds. It showed the way to reconciliation with the vast bulk of non-Catholic Christians who do not share the Catholic conception of the place of natural law.

All of this developing situation has now been set at nought. The known views of such senior Cardinals as those of Vienna, Utrecht and Malines, of many bishops throughout the world, of the Papal Commission, of moral theologians of the highest repute from such widely differing schools as those of the Gregorianum in Rome and Maynooth in Ireland, of the laity as expressed at the Lay Congress in Rome last year, have been put down as of no account.

It will be taken by some as a magnificent gesture of defiance of the ways of the modern world infiltrating the Church – a voice crying in the wilderness. Affection and respect for the lonely figure of Paul VI almost impel this response.

What happens, we might ask, if his voice is not heeded? Where is the seat of authority, the voice of Peter? These are real and urgent questions, no less anguished than those which must now come from people who hardly know what to do in the face of this apparently absolute prohibition put upon the spontaneity of their love-making.

To both it must be said that there is no finality in the search for God’s truth. The Pope’s weighty words take now a dominant place in a great debate. He makes his appeal to reason and the natural law: it is the prerogative of every man to appeal to the same: the debate will continue.

The Pope appeals to former Encyclicals, above all to Casti Connubii. They have been under increasing scrutiny with the passing years and so it is not surprising that his own is already coming under the same fire – intensified by modern pressures. This will raise, inevitably, questions as to the status of Encyclicals, their authority and binding force. Whether they will be devalued or endorsed we cannot predict. A new chapter in the relationship of the Pope with his bishops and with the faithful at large has now opened on a sombre note. There will be doubt and dismay about the Church herself amongst her more reflective members, a new bravado in some sectors: a mutual mistrust.

Loyalty to the faith and to the whole principle of authority now consists in this: to speak out about this disillusion of ours, not to be silenced by fear. We who are of the household and can think of no other have the right to question, complain and protest, when conscience impels. We have the right and we have the duty – out of love for the brethren. Quis nos separabit?

No comments:

Post a Comment