The Tablet

Summer lightning: the storm over birth control and Catholic Church 50 years ago

Marches, teach-ins, petitions, boycotts, grass-roots collectives: radical initiatives that readily conjure up images of the May 1968 protests in Paris or the student sit-ins at the London School of Economics. Yet, in the summer of 1968, the publication of a papal encyclical was to provoke similar forms of protest.

This unlikely affront to the public conscience was, of course, Pope Paul VI’s encyclical letter condemning the use of artificial contraception, Humanae Vitae, which was published on 29 July. But while the restless radicals of the secular Left tended to be cosmopolitan intellectuals and avant-garde youth, the Catholic “counter-culture” was thoroughly conventional, respectable and middle-class.

The scale of the revolt, which encompassed laity and clergy, was national in reach and local in action, and drew on tight-knit parochial, professional and educational networks. Though it might be tempting to cast this moment as a Catholic equivalent to the politically left-wing and theologically liberal “South Bank religion” of John Robinson and Mervyn Stockwood, these dissenters’ heartland was suburban London and Surrey.

Defenders of Humanae Vitae tended to dismiss the overwhelmingly negative commentary and rarefied analysis of the encyclical that dominated the news columns of the national press (especially The Times, under the editorship of William Rees-Mogg) as the bleating of long-haired intellectuals and youthful clergy seduced by the spirit of the age.

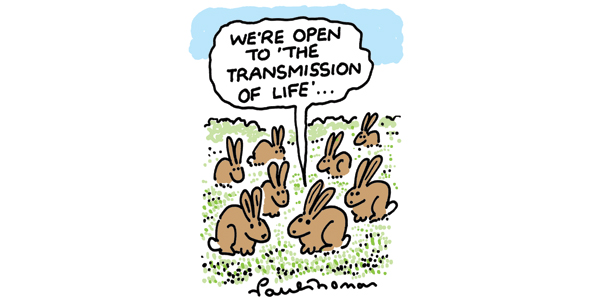

But it quickly became clear that those agonised or angered by the ruling – that “each and every marriage act must remain open to the transmission of life”– were not just the broadsheet-reading chattering classes. They were mainstream, church-going Catholics, whose preferred form of opposition was quietly to make their own decisions about whether to use artificial or natural means – while the Pill was banned, use of the “safe period” was permitted by the encyclical, a distinction few found plausible – to plan their families or to drift from the Church altogether.

For those who stayed and who were to find themselves at the heart of the storm, a vision of the post-conciliar Church was at stake. Could one dissent from the teaching of the magisterium and still be a Catholic?

Writing in the correspondence columns of The Times to explain why his critique of the papal encyclical (which he had commenced on the day of its release with an excoriating condemnation on the BBC’s Panorama programme) was neither insolent nor disloyal, the Conservative MP Norman St John-Stevas used the analogy of the household.

He contrasted what would be insubordination from a subservient slave with the legitimate disagreement of an adult son with his father, and concluded: “This is at the heart of the present dispute. The laity have come of age, they are expressing their minds to the Holy Father. This is an act of love and trust not of contumely and insult.”

Hundreds of letters to the newspapers and extensive coverage on television and radio of Catholics expressing confusion and disappointment followed in the weeks after the encyclical was released, prompting one writer reviewing the response to Humanae Vitae across Europe to observe: “UK reaction most intense”.

Into this media melee, on 9 August, the Archbishop of Westminster Cardinal John Carmel Heenan offered a pastoral letter which counselled married couples “not to despair” and, above all, “not to abstain from the sacraments”. Addressing those – including the majority of the bishops and theologians Pope Paul had consulted before he issued the encyclical – who believed the time had come for a change to the Church’s condemnation of all forms of artificial contraception, Heenan flatly declared that “the law of God cannot be decided by majority vote”.

An ad-hoc committee had already been formed with the aim of supporting dissident clergy. The organisers were a “who’s who” of Catholic professional life: Hilary Armstrong (philosopher and classicist), Ronald Brech (economist and organiser of “New Pentecost”), Robert Nowell (editor of Herder Correspondence and former Tablet assistant editor), the publisher John Todd and many associated with the Newman Association (including Oliver Pratt, Ianthe Pratt, Anthony Spencer and Monica Lawlor).

The group’s letter in The Guardian urged clergy not to court suspension by dissenting publicly but rather to send them a brief statement, which would be published without attribution. At a press conference in late August, they were in a position to communicate the views of more than 100 priests and 150 lay people who had written to their London N6 postbox.

Meanwhile, other activities drew prominent media coverage: a “collection strike” in Salisbury; the collation of a national register offering accommodation to suspended priests; the establishment of an “Association for Ex-Clergy” (run by Malcolm Magee OP, former Prior of the Holy Cross, Leicester) and the creation of a “Freedom of Conscience Appeal Fund” to support clergy transitioning from active ministry. Priests in Buckinghamshire, such as Fr David Woodard and his curates, Nicholas Lash and Vincent McDermott, organised lay study groups and made a parochial submission to the Northampton Diocesan Commission.

Perhaps the most prominent and well-orchestrated of all the protests was the day of “pray-ins” at cathedrals across the country. Spokesperson Patricia Worden told reporters: “We believe that love has the first place in marriage, that Humanae Vitae is by no means the last word on the Christian view of sex and marriage, and that the yoke of Peter should not be heavier than the yoke of Christ.”

A leaked working paper from the Laity Commission (a newly-established consultative body to the bishops’ conference) asking a series of awkward questions about the status and substance of the encyclical confirmed the sense and scale of the crisis. Public attention now centred on an event on the evening of 13 September organised by the London Circle of the Newman Association. More than 1,000 people – laity, clergy and women Religious – crowded into the Methodist Central Hall, Westminster, for a four-hour discussion and debate. The speakers included Dr John Marshall, the distinguished English neurologist who had been a member of the commission established by Pope Paul to examine the question of birth control, and who had expressed shock at finding that the resulting encyclical contained “no theological argument to support the view that contraception is contrary to the natural law”. Fr Peter de Rosa (the vice-principal of the short-lived Corpus Christi College for religious education that Cardinal Heenan had set up) and Fr David Woodard joined him in attacking the teaching of the encyclical. Douglas Woodruff (former editor of The Tablet), Fr Clement Tigar and Christopher Derrick spoke in its defence.

Reports described the exchanges as a “debate within a family, free from rancour, serious but rarely solemn … and the type of discussion that would heal rather than open wound.” A woman in the audience asked the all-male panel if they had considered how the female partner’s enjoyment of sex might illuminate the debate. The chair hastily moved on to the next question before they could answer.

Public dissent reached a crescendo in October when The Times published a joint letter from 55 priests stating that they could not give loyal obedience to the view that all artificial means of contraception were wrong in all circumstances. Five days later, a joint letter from 76 lay Catholics followed. In it, figures such as Graham Greene, Rosemary Haughton, Lady Antonia Fraser and the educationalist John Newsom stated that they found the distinction made in Humanae Vitae between the rhythm method and the Pill “untenable and the arguments to support it unconvincing”.

The bishops of England and Wales attempted to dampen the flames through a carefully worded joint pastoral statement on 24 September. Cardinal Heenan spoke on behalf of the bishops in late October. There should be no more “scandal” to the Church, he said; henceforth, priests were to refrain from criticism of Humanae Vitae in public, or in the confessional.

It is this aspect of the encyclical storm that is little remembered. Juxtaposed with the passionate dissenting voices of Catholic couples was media coverage of the plight of dissenting clergy.

The case of the “rebel priest”, Fr Paul Weir of St Cecilia’s, Cheam, attracted particular attention. From early August, when Fr Weir made public his stance on the encyclical, the handsome, charismatic 31-year-old curate became a cause célèbre. Equally under the spotlight was the arch-conservative Archbishop of Southwark, Cyril Cowderoy. While other south London clergy were censured or suspended for their assertions of freedom of (clerical) conscience, including Kenneth Allen (Coulsdon), who co-ordinated the joint letter of the “55” and Mgr Antony Reynolds (Borough), who was forced to retract his published calls for a “week of prayer” in an open letter to the Pope, Fr Weir became the poster boy for the progressive cause. Petitions were launched in the parish and the youth club organised a 100-strong march from Westminster Cathedral to St George’s Cathedral, Southwark, with protesters carrying banners stating: “Has Not Father Weir Suffered Enough?” and “We Want Father Weir Back”.

Archbishop Cowderoy’s pastoral letter of 16 August 1968 castigated the actions of such “disobedient priests” who “in a spirit of bitterness and want of reverence and in some cases with a lack of maturity” are “false and devious advisors”, “misleading some of our poor, simple people” with “unfounded hope”.

A planned 24-hour occupation of Southwark Cathedral followed, with protesters marching under the banner “1968 Youth Need 1968 Priests”. But, after a few hours, police forcibly ejected those gathered in prayer for trespassing. Louisa Peachy, then aged 17, gave a statement to the press: “This is not only a protest in support of Father Weir, but also a protest in support of free speech. We believe that everyone in the Church should have the right of free speech.”

Fr Weir’s cause, which continued to be reported into November, when he was re-assigned to a Kent parish, was symptomatic of the Humanae Vitae controversy, which pitched the right to speak freely and responsibly about contested matters of teaching with a Church determined to stifle debate.

From the distribution of red car stickers sporting the slogan “Freedom for R.C.s – No Inquisition”, to the so-called “Northern Rising” centred on the Benedictines at St Mary’s Highfield, where Sebastian Moore was the parish priest, and the chaplaincy at Liverpool University, there was a demand for greater transparency and consultation. There was a feeling that the conciliar Church was at stake.

What were to turn out to be the death throes of the debacle were played out in Nottingham in November, where Bishop Edward Ellis had suspended four diocesan clergy who had publicly dissented from the encyclical. The ad-hoc committee organised yet another teach-in, culminating in a document protesting about the priests’ suspension, called “Four Honest Men”.

At the close of the year, Cardinal Heenan gave his celebrated television interview to David Frost. He was closely questioned about what a confessor should do when confronted with a husband or wife who used contraception in good conscience.

His response, after a pause, that he should say, “God bless you” and allow them the sacraments, confirmed Bishop Christopher Butler’s assessment that “we are groping about in a situation which is unparalleled in our Catholic experience”. Another bishop, later archbishop, Derek Worlock, while accepting the teaching of Humanae Vitae, added carefully that contraception was “not the acid test of Christianity”. The English bishops had arrived at a sort of settlement: a space had been created for Catholic couples who could not in conscience assent to the teaching of the magisterium that the Pill could not be used in planning their families to continue to come to Mass and receive Communion. For their priests, however, public dissent from the encyclical would never be condoned.

When news of Humanae Vitae first emerged, Bishop Thomas Roberts SJ reflected: “A storm has broken out, and it will grow … but a mighty good thunderstorm clears the air.” In the years following, there have been distant rumbles of thunder and the occasional flash of lightning. Yet, 50 years on from the hubbub in the press and the fiery fury in the suburbs, such impassioned lay revolt now feels like ancient history.

Alana Harris is lecturer in modern British history at King’s College London. She is the editor of The Schism of ’68: Catholics, Contraception and Humanae Vitae in Europe, 1945-1975, published by Palgrave Macmillan, £99 (Tablet bookshop price, £90.50). She is currently collating an oral history of Catholic responses to Humanae Vitae.

No comments:

Post a Comment