28 March 2018 | by Luigi Gioia

The Tablet

'Your love for one another' – is this the only real 'proof' of the Resurrection?

Luigi Gioia OSB on how inclusive and non-judgmental love opens eyes to the presence of the risen Christ

If we were to try to revisit the series of events surrounding the

aftermath of Jesus’ death with the eyes of someone who does not believe

in God, we might be in for a surprise. Far from resisting this approach,

the Gospels anticipate it by relating the bare facts surrounding the

mysterious disappearance of Jesus’ body: the empty tomb; the large

entrance stone rolled away (Mark 16:3f); the strips of linen and the

burial cloth inexplicably left behind (John 20:6f).The Gospels also tell us that within a few hours two competing narratives had started to spread: some suspected that Jesus’ disciples had come at night to steal the body while the guards were asleep (Matthew 28:13); others, especially a group of women, pretended to have seen angels and even Jesus himself alive (Luke 24:23f). It would be the ideal scenario for one of Arthur Conan Doyle’s artfully crafted detective stories: bizarre circumstances, tenuous and clashing clues, wrapped in an aura of mystery. It would take a Sherlock Holmes to solve the riddle.

The mention of Conan Doyle’s hero is more than a diversion here. Holmes personifies a positivist approach to reality and history that rigorously separates facts (such as the empty tomb) from values (a belief that Christ is risen). According to Holmes’ methods of deduction, we can take into consideration only that which can be proven true or false empirically, and, in any case, whatever our conclusions, we cannot infer beliefs or behaviours from them. Even in the absence of any plausible explanation for the empty tomb, we cannot rely on subjective accounts of visions of angels or of someone coming back from the dead. These things do not happen today and cannot therefore have happened in any other time in history.

The lack of consistency between the accounts of the Easter story in the four Gospels seems to further complicate the story. And besides the material discrepancies, a striking conundrum besets the Resurrection narratives: if and when the risen Jesus appeared, why did the people who had known him and lived with him for years doubt his identity (Matthew 28:17) and struggle to recognise him? He is mistaken for a gardener by the eager Mary (John 20:15); he entertains the unsuspecting disciples of Emmaus for hours as a perfect stranger (Luke 24:13-35); he sounds strangely unfamiliar – more like an intrusive know-it-all – when he gives advice to his closest friends and fishermen John and Peter (John 21:1-10). He is alive in a way which is unheard of: he can prepare breakfast and enjoy cooked fish, but he is also able to pass through closed doors; he sports gaping wounds, but they do not hurt him any more.

The credibility of these accounts seems compromised when we are told that the mysterious character who appeared to the disciples after the traumatic events of Good Friday is identified as Jesus because those who meet him experience a burning of the heart (Luke 24:32). We picture here Sherlock Holmes’ condescending shrug. They felt something when they met this man? Feelings are notoriously unreliable: they have hidden causes in our subconscious; they are influenced by social expectations; they are easily manipulated. Desperate, damaged or simply unsatisfied people can be led to feel and believe almost anything, and to persuade themselves that it is the truth. The human capacity for self-delusion is boundless.

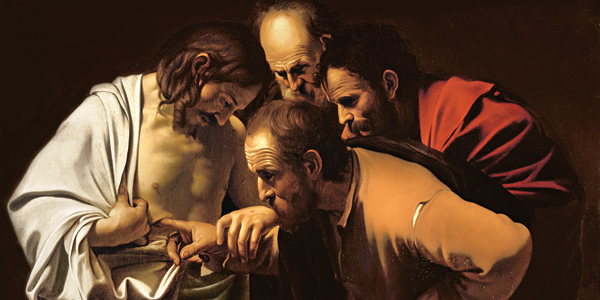

But the authors of the Gospels do not bother with apologetics: they are not afraid of competing narratives; they acknowledge the ambiguities of the encounters with the risen Jesus; they do not disguise the role played in the story by the disciples’ feelings. For them belief in the Resurrection makes sense, but it does not rely on deductive reasoning. The trigger is described as a moment of sudden realisation, captured in some of the most moving exclamations in Scripture: “My Lord and my God!” from Thomas (John 20:28), “Rabboni” from Mary (John 20:16) and “It is the Lord” from John and Peter (John 21:7).

The burning of the heart plays a role in this realisation but its full significance is appreciated only retrospectively: “Were not our hearts burning within us while he talked with us on the road?” (Luke 24:32). In other words, feelings play a role only in relation to another much more decisive factor, described through the suggestive image of eyes suddenly being opened: “When he was at the table with them, he took bread, gave thanks, broke it and began to give it to them. Then their eyes were opened and they recognised him” (Luke 24:30f).

The belief that Jesus is alive is portrayed as a sudden realisation prompted by an action apparently unrelated to the nature of the Resurrection – the sharing of a loaf of bread. This simple action enables them to make sense of the extraordinary and profoundly disturbing events of the previous few days.

In our everyday lives we have similar experiences. After weeks of painful meandering, the decisive breakthrough for the argument of my doctoral thesis came to me as I was flicking through a fashion magazine. We call this a “eureka moment”: a random trigger suddenly makes sense of a complex and baffling series of facts and events in a way inaccessible to rational reasoning. If we regard the “breaking of bread” as too unempirical a trigger for the eureka moment of the Resurrection, we are in good company: remember the eureka moments prompted by a hot bath for Archimedes, a falling apple for Newton’s theory of gravity and the oars of a boat for Mahler’s 7th symphony?

Eureka moments might seem random but they are not irrational or arbitrary. They only happen to people who have strenuously toiled with an issue for a long time. Louis Pasteur famously said that chance favours the prepared mind. In the same way, the eureka moment of faith in the Resurrection only occurs after sustained interaction with Scripture: “Beginning with Moses and all the prophets, Jesus interpreted to them what referred to him in all the Scriptures” (Luke 24:27). And we are told that it was only after Peter had led his listeners on an extensive journey through Scripture that they were “cut to the heart” (Acts 2:37) and started to believe.

Faith in the Resurrection requires narrative, interpretation, explanation, listening, questioning, doubting. It does not come as the mere logical conclusion of an argument. It takes facts and logical argument into consideration, and it is accompanied by feelings, but these are not decisive. It needs something more – a catalyst – that all of a sudden gives a coherent shape to all the scattered and previously disjointed pieces of the puzzle. For the disciples at Emmaus this catalyst was the breaking of bread. And for us too, the eureka moment of faith in the Resurrection should be expected not in a bathtub or under an apple tree, but in the breaking of bread at our Eucharistic celebrations.

Looking for inspiration in our liturgical celebrations might seem unrealistic: they are often either too casual or too obsessively ritualistic. We think that we have participated in the Eucharist just because we have been physically present, listened (or often endured) the sermon and taken Communion. The breaking of bread Jesus asked us to repeat in his memory can act as the eye-opening catalyst for our faith in the Resurrection only if we have been prepared by the reading of Scripture followed by a rich, well-prepared homily.

Then, the heart has to be fed by heartfelt and joyful exchanges of the sign of peace, reinforcing a sense of belonging that will spill over into our lives outside the celebration of the Mass. Finally, we have to receive the Eucharist not just by eating it but by embodying its dynamic within our lives. The breaking of bread is Jesus’ gift of himself to us. When we take part in it, we accept that we are to live not just for ourselves but for everyone else, in countless and unforeseeable moments, big and small, in our daily life.

In the end this is why the gospel writers were not afraid to acknowledge the ambiguities and inconsistencies in the narratives of the Resurrection. They knew that the eyes of the world would be opened to the presence and action of the risen Christ in history only when it could be recognised in the solidarity shown by Christian communities, and in the inclusive and non-judgmental love that startles those who come close to us and makes them feel truly welcome. This is the only real “proof” of the Resurrection that opens the eyes as it makes our hearts burn: “It is your love for one another that will prove to the world that you are my disciples” (John 13.35).

Luigi Gioia is research associate of the Von Hügel Institute for Critical Catholic Inquiry, St Edmund’s College, Cambridge, and the author of Say it to God: In Search of Prayer. Follow him on Twitter.

No comments:

Post a Comment